As I’ve worked my way through the volumes of Form Stallion Register, I haven’t commented each time on repeat entries. Mexico was in each of the first three, and a few of the star performers (e.g. Jungle Cove and Elliodor) are in II and III.

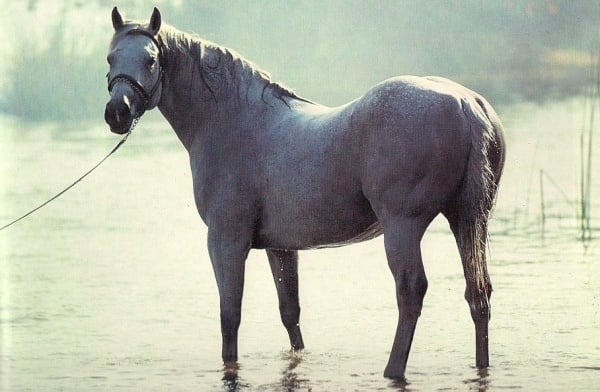

Russian Fox (Pic – Supplied)

Oscar Foulkes writes that in working through Volume III, one of the features that jumped out at him was the large number of stallions that had already done duty elsewhere in the world.

For a few of them, their relocation was a response to their progenies’ performance here.

The sires of Foveros, Spanish Pool, On Stage and Devon Air all made their way to South Africa. In the case of these, just Averof could be regarded as making a positive local contribution, with just under 6% stakes-winners (from foals). On the whole, other than a couple of star performers, there just wasn’t enough depth in their overseas record to warrant their importation.

Making the case for the importation of established stallions, Condorcet and Home Guard performed creditably, while Singh left three Grade I winners from four local crops numbering just 128 foals. Northfields was imported at age 15 and did not repeat his overseas record.

The star of this firmament, though, was Dancing Champ. His record of 61% winners and 10.7% stakes-winners included the likes of Olympic Duel and other top middle-distance performers.

Dancing Champ (Pic – Supplied)

What set his overseas record apart was a cumulative AEI of over 2 (i.e. the average earnings of his runners, expressed as a ratio of all runners over the same period, was double the average).

Equally important, he was improving on his mares (in other words, their results by other stallions were inferior to Dancing Champ). Stallions like this are not easily let go of, for obvious reasons!

While these factors become moot once a stallion has runners, Dancing Champ was a top-class racehorse by Nijinsky, from an excellent family. Like Jungle Cove and Elliodor, he ticked a lot of boxes.

In the same era, we had two other successful sons of Nijinsky.

The more conventional choice, Peacetime, was imported at a cost of R2.5 million (over R58 million when adjusted for inflation).

He earned a Timeform rating of 125 with top-class British form over middle distances. His abbreviated stud career left the Grade I-winning Saintly Lady, as well as percentages that exceeded breed averages. Given his credentials, though, one can’t imagine that expectations of his stud career were anywhere near being matched by his final record. He earns some posthumous credit by siring the grandam of Vercingetorix.

On the other hand, Russian Fox started his career in France, ending up on the Turf circuit in Florida, although outside Graded stakes company.

It takes a bit of careful form study, but he showed smart ability in Allowance races.

He wasn’t the typical Nijinsky physical type, in that he was a smaller, closer-coupled horse more typical of his grandsire, Northern Dancer. Bred to the poorest of mares, he fired with his first crop.

Northern Guest (Pic – Supplied)

There seemed to be an affinity for mares by sons of Drum Beat, or other Fair Trial line stallions. One would have expected his results to ramp up as he covered better mares, but for unknown reasons he stayed in the above-average category with 56% winners and 5% stakes-winners. Interestingly, the Fair Trial nick wasn’t utilised to the extent one may have expected, and in some years he covered no Fair Trial line mares at all.

Of course, Russian Fox was the broodmare sire of Mother Russia (and her grandam was by Drum Beat).

Russian Fox was initially purchased (at one-sixth of the cost of Peacetime) by Piet Nel, a man characterised by his bushy grey moustache framing a playful smile. Matching his down to earth nature, he was often seen in shorts and red vellies.

He came to racing and breeding from the somewhat scrappy world of trucking. One wouldn’t say that either he, nor his similarly grey stallion, came from the elite inner circles of the industry.

Greys from the fringes feature again, in the form of the grey I’m Exclusive (purchased at one-tenth of the cost of Peacetime), a US-bred and raced son of Exclusive Native that stood at Loretta Krein’s Windy Way Stud.

Pictures of him show a deep-chested, muscular horse with severely bowed tendons. He couldn’t have been a sound horse, being unraced at two, starting just once at three (finishing 2nd), five starts at four (in the money every time, including breaking his maiden), and three at five (two wins). He must have had ability, though, to justify keeping him in training all that time.

He sired just four crops of 121 foals.

When you look at the sires of the mares he covered, you could almost imagine Loretta resorting to rounding up stray Thoroughbreds in the Port Jackson bush that characterises the area around Philadelphia, Atlantis and Mamre where her stud was located. You may not even have found pedigrees as lowly in bush racing. And yet he sired eight stakes-winners, including the Queen’s Plate winning I’m Taking It, as well as several other Grade I performers.

The suggestion is that some minimum of above-average racing talent, pedigree and looks are required. It does not appear to be necessary to display the racing talent in Grade I races, but it must be there. If the stallion has the ability to transmit that to another generation, he will, almost regardless of the opportunity he is given.

There was comparatively large cohort that had been imported for racing purposes and were then retired to stud. Three were sons of Sharpen Up, one by Red God, as well as Derring Do, Habitat and others. The sole relative success was Fine Edge, with 55% winners and 5% stakes-winners. In retrospect, perhaps they needed just a little more racing ability to pass on to their progeny.

Taban, a super son of Home Guard (Pic – Supplied)

Readers familiar with this era may be wondering when I’m going to get to Northern Guest, a popular Champion Sire.

He had 19 local crops, totalling 1096 foals. The high points were siring the likes of Senor Santa, Northern Princess and a few others, because for the rest his percentages were dead-on average for the breed: 51% winners and 3.8% stakes-winners. In the mid-90s he had three crops of nearly 100 foals, when most stallions were producing less than half that number.

The triumph of hope over evidence was also exemplified by Golden Thatch’s full-brother, Waterville Lake. Largely on the basis of siring the Champion Sprinter, Flobayou, his career extended to 13 crops, cashing in at a below-average 47% winners and 2.7% stakes-winners.

Any look at the stallions of Volume III would be incomplete without recounting the tale of Argosy.

By a Triple Crown winner, Affirmed, this half-brother to another Triple Crown winner, Seattle Slew, was purchased by a syndicate headed by Graham Beck and the Birch Bros. This was just after the sale of Wolf Power, which left the Birches with a looming tax problem. This could be remedied by the purchase of a stallion, which was a perfectly sensible way of dealing with the issue.

However, they were advised (by smart banker-types, no doubt) to fund the purchase with a low interest, dollar-denominated loan. No forward cover was in place, which nearly doubled the final cost when the Rand fell out of bed soon after.

As if the search for good stallions wasn’t already sufficiently difficult, risky, and expensive.

Affirmed’s Triple Crown saw him doing duel with Alydar. I highly recommend a detour on YouTube, to watch the two doing battle, two mighty chestnut colts descending from Raise A Native (Affirmed by Exclusive Native and Alydar by Raise A Native himself).

Ultimately, the victor was the lesser stallion, with Alydar’s progeny achieving far more than those of Affirmed. Argosy was from Affirmed’s first crop, so this was not known at the time of his purchase.

Author’s Footnote:

Volume III of Form Stallion Register was published in 1986, four years after volume II.

Every iteration represented a major step up in the technical aspects of publication. Its editor and creative director, Charles Faull, was obsessed with the very top end of what one could call the art end of the publishing industry. So, Volume III was printed in full colour on the best paper, with exacting standards throughout its production, from the processing of colour film to photo printing, to design, to repro, to printing and more. A few years ago, I saw Mr Borgelt, the owner of the company responsible for the binding of the volume, in my local shopping centre. I was going to re-introduce myself, and then thought better of it for fear of sparking a full-blown PTSD episode. Charles pushed all these suppliers to deliver at the absolute maximum of their performance, and it shows.

This is probably the most over-engineered stallion register of all time, in any country. It’s an extraordinary resource. Like previous volumes, many pages are devoted to ancillary information, delivering on Charles’ maxim: “Everything worth doing is worth overdoing.”

Not only the technical aspects received that kind of attention. The same attention was paid to the content, for which I’m extremely grateful, as I sift through the stallion successes and failures.

For example, Jungle Cove’s track record was completely redone from the slimmer version in Volume II. His class as a racehorse is easy to see. Mexico’s track record was also expanded. Plum Bold, despite his re-export to the US in 1980, received an entry (his were stellar stats, by the way, with 66% winners from foals, and over 12% stakes-winners).

It is thanks to Charles’ insistence on the inclusion of additional information that I have the initial purchase prices of stallions, as mentioned above.

As far as content was concerned, the research team had lost Robin Bruss, but gained Jeremy Nelson, James Bester and Victor Connolly, all of whom have parlayed their Form experience into achievements elsewhere. The stalwarts, Jehan Malherbe and Norman Daniels, remained in place. I must have contributed to some of the research (and a few of my stallion photographs were used).

I should add that when you get up close and personal with the gritty nature of research, it changes your relationship with the data. Well, it did for me. When it came to compiling stud records, this was the process:

- Using the supplement to the Stud Book, which contains the foals born in a year, listed by stallion, write out a sheet separating colts and fillies.

- Look up every start of every foal, using the Racing Calendar, and record the starts, wins, black type races etc.

It’s no surprise that I have become attuned to a stallion’s strike rate. Are the winner and stakes-winner percentages (from foals) exceeding averages? Does the level of out-performance put the stallion into an elite category?

All that manual work eventually became ARO.co.za, which has been an invaluable research tool in enabling me to quickly draw conclusions about the stallions’ performance at stud.

This was long before the days of Photoshop.

The backgrounds of most of the stallion pics were airbrushed by a lovely gentleman by the name of Mike Chase. For reasons unknown to me, Proclaim’s picture was not airbrushed. While you can see the tip of the nose and chin of the person holding the stallion, the giveaway of the identity of the mystery ‘groom’ are the pointy white shoes that James Bester wore at all hours of the day (and especially at night).

Ed – Courtesy of Oscar Foulkes, Volume Four sees the arrival of grandsons of Raise A Native, through Alydar and Mr Prospector…