In this business, none of us should overestimate our powers of prediction. The best we can do is to make better assessments of the ‘risk profile’ of each yearling/stallion/broodmare. Our best tools are experience and context, couched in all the humility we can muster.

With context in mind, Oscar Foulkes writes that he followed on his exploration of stallions in Volume I of Form Stallion Register – read ‘Stallions – What’s The Recipe?’ here – by taking a dive into Volume II, published in 1982.

The volume includes 207 stallions, with a significant representation from across the Limpopo – presumably the product of Robin Bruss being part of the editorial team.

There was, again, a large number of South African-bred stallions that retired, largely without success, although few of them received the kind of support given to Over The Air, who ultimately recorded stats that couldn’t even match breed averages, let alone surpass them.

The Champion Jet Master (Pic – Supplied)

The heavy lifting was still being done by imports; we had to wait a few more decades for Jet Master, Dynasty and Captain Al to come along!

When it came to opportunity, the good stallions somehow found their way beyond small numbers. Yes, it’s a harder way of doing it, especially these days when buyers hold a stallion with under 20 foals to the same numerical standards as ones with 100.

Somehow the good stallions produce top-class runners from small numbers, even if the quality of the mares is not good.

Elliodor (Lyphard-Ellida)

This era delivered the poster child for stallions that got there with small numbers. Elliodor’s crop sizes were 14-10-5-18.

He was lucky that nothing happened to Model Man (one of three stakes-winners in his first crop), although with nine stakes-winners from just 47 foals in his first four crops, he would have drawn attention anyway. He had 53 foals in his fifth crop, and after that he was off to the races (in every sense).

Elliodor was a Pfaff homebred, retired to Daytona Stud after breaking down in his third start at two.

John Kramer – suggested the Elliodor mating (Pic – Bay Media)

While he didn’t win a Group race, he showed enough promise in his maiden win over 1600m to earn a Timeform rating of 114, along with the comment that he would “likely make a smart three-year-old”.

John Kramer, then stud manager at Daytona, says that he suggested the mating that produced Elliodor on the basis that his dam was a big rough mare, and Lyphard was a neat, high-quality individual.

Based on pedigree, looks and racing promise, Elliodor was not a surprise success, even if it took a while for breeders to take note.

On the other hand, Complete Warrior, a stakes-placed winner of Allowance races, had to get past the stigma of being a son of one of Bold Ruler’s lesser sons, in Dewan. Reflecting this skepticism, his crop sizes were 12-21-8-15.

Sea Warrior wins the 1986 Richelieu Guineas (Pic – Supplied)

Guineas winner Sea Warrior popped up in his first crop and then Queen’s Plate heroine Wainui in his fourth, which set him on his way. Complete Warrior never reached the heights of Elliodor, but he is immortalized as the broodmare sire of the great Captain Al.

His grandam was a Nasrullah half-sister to Buckpasser, which resulted in an interesting pedigree pattern with Al Mufti (the sire of Captain Al). At the time, I thought it interesting that Complete Warrior had close inbreeding to Nasrullah. Maybe that was ultimately significant.

Returning to Daytona Stud, where several stallions did duty, each with some degree of success.

A bygone era – Daytona Stud

All of them had enough going for them to earn a chance at stud, even if they didn’t cover large books of mares.

In a way, this is a little like modern venture capital investing in tech or biopharmaceuticals. One doesn’t know where the next big thing is coming from, so make a bunch of small bets and see what comes off. The few successes end up paying for the failures.

Foveros went to stud in 1982, having established himself as the best middle-distance horse in the country. He was also extremely good looking. This is where the obvious ‘pro’ factors end.

Foveros

His sire, Averof, was nowhere near being a world-leading stallion, and even joined Foveros in South Africa in 1983. But succeed Foveros did, with Enforce and Aquanaut leading the way for his first crop of 29 foals (followed by full books thereafter).

With Foveros on his way to success, his owners moved him to KZN to benefit from the financial incentives offered by the province’s breeders’ premiums.

The opposite happened, in 1979, when Jungle Cove was relocated from KZN to Maine Chance. While Jungle Cove was a top-class racehorse by one of the 20th century greats, in Bold Ruler, he was long backed with a very plain head.

Nevertheless, Jungle Cove was a much more predictable success than Foveros. Up to that point, he was the best-performed son of Bold Ruler to stand at stud here. It bears mentioning that no equivalent son of Northern Dancer was at stud in that time.

There was another, albeit less auspicious, stallion move that took place, which carries a lesson for me personally. In 1984, my parents agreed to stand Divine King, who was then the dominant stallion in Zimbabwe -to the extent of 70% winners from foals and nearly 12% stakes-winners.

If one was circumspect about sons of Averof, one certainly didn’t want a son of Divine Gift, even if he was a typically good-looking sprinter. After all, the classics were being won by sons of Northern Dancer and Nijinsky.

The writer, Oscar and Mom Veronica Foulkes (Pic – hamishNIVENPhotography)

Despite my youth – ’84 was my Matric year – I didn’t hold back in telling my parents what I thought. His South African record (59% winners and 5.8% stakes-winners) ended up being some way off his Zimbabwean stats, so I wasn’t entirely wrong, but in our current stallion crisis I’d be grateful for access to a stallion with these stats. I apologise to all concerned.

The big learning is that perhaps one needs an incubator of sorts, similar to the tech world. To start, it’s a high-risk venture capital exercise in which a diversity of prospects is given a chance (even if they are by Averof or Dewan!). Once there is a proven record, it moves into the realm of a kind of private equity buy-out (i.e. possible stallion relocation).

In one form, or another, the stallions I’ve mentioned here have gone through versions of this kind of process. In theory, this is happening today, with a variety of stallions being retired to stud and then we await the outcome. However, the stakes these days are much higher, and we somehow have a much narrower band of experimentation. Also, there is pressure for stallions to cover more mares.

One of the main rules of trial is to change direction – or stop – when there is adverse feedback. It’s very hard to do this, so we always seem to push on for an extra year or two. Sometimes this decision is taken out of our hands by the early death of a stallion. It now seems to be a rule that if a stallion dies early, he will be successful.

Two notable examples in this era were Brer Rabbit (60% winners and 7.7% stakes-winners from just five crops) and Rollins, whose five small crops produced 10% stakes-winners.

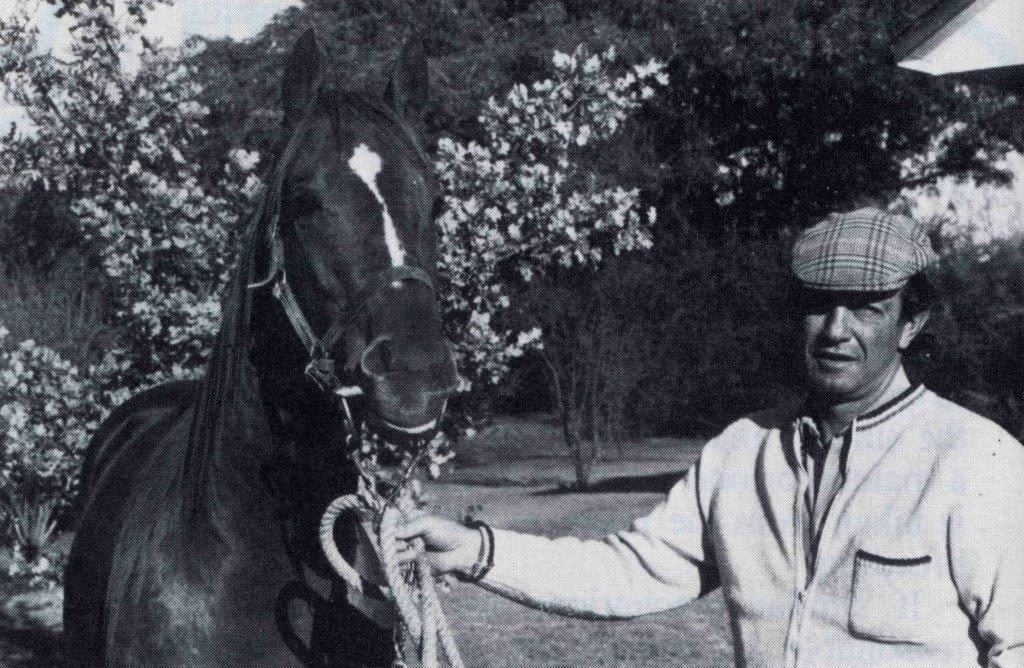

Lowell Price with Brer Rabbit (Pic – Supplied)

His contribution to the breed was siring the dam of Jet Master. When I think back to the light-framed horse that Rakeen was in training, it’s hard not to believe that the unraced, but good-looking and superbly well-bred Rollins played an outsized role.

As I went through the stallions in Volume II, there were a dozen (or maybe more) that were good racehorses by good enough stallions (even if one could poke holes in their sires’ status with the benefit of hindsight). Some of them were qualified successes – in other words, their importation was justified.

By way of example of stallions that served us well at a level between basic success and Champion Sire status, I give you Folmar and Del Sarto.

Neither of them went to stud with great fanfare. Both were smart racehorses with top pedigrees, siring more than their fair share of Grade I winners. Having stallions like this available to breeders in the 80s may have played a part in preventing the kind of extreme polarization we are seeing these days.

Once again, many sprinters were retired to stud, both local and imported.

Golden Thatch – standout results for speed (Pic – Supplied)

Golden Thatch had by far the best credentials of all the sprinters that were imported and delivered standout results.

The low success rate of this category did not point to this being a strategy that could be relied upon to beat the odds. However, the pedigrees of the failures were not inspiring, and I wonder about the role played by that factor.

Brer Rabbit, mentioned above for his abbreviated stud career, may have been put into the sprinter category by some. However, he had good form over 1500m in Italy prior to continuing his racing career here, and even finished a close third in the Queen’s Plate over 1600m. One has to wonder about the importance of that extra bit of stamina.

In assessing stallions, the best I can claim is a framework, a general guide for want of a better description. Foveros was a rare example of a stallion who outperformed an initial assessment of his credentials (i.e. based on the quality of his sire). Mostly, the leading South African stallions have come from the cohort of talented racehorses, by world-leading sires. While physical perfection does not appear to be a necessity, assessing horses’ conformation (or ‘presence’, if one isn’t going to go into structural detail) is so subjective that I’ll perhaps return to this element on another occasion.

I leave you with an apt quotation attributed to the economist John Maynard Keynes: “When the facts change, I change my mind.” It’s as appropriate to the practice of selecting stallions as the forecasting of macroeconomic indicators.