“All games have rules. In racing, huge sums of money are at stake, and the livelihoods of licenced participants can be in danger, so it needs good rules, which are fairly and consistently administered” – Ken Stewart, Chief Stipendiary Steward, Jockey Club of South Africa, from his book “Racing Control”, published in London, 1974.

Opening Page of the NHA’s Annual Report

I’m writing these articles on the history of the NHA not to challenge but to inform and educate and try to make sense of where we stand in this industry by asking why and how.

I have been involved in racing all of my life and my father registered his silks as an owner/trainer as far back as 1943, second longest standing silks behind the Oppenheimers in 1937.So everything long term.

Robin Bruss writes that history provides perspective, trends have meaning, lessons of the past can guide us in the future, either to learn from past error, or at least to avoid repeating it!

I don’t consider that I know everything, but at least I try to live in what Socrates called “the considered life.”

That is, to make decisions based on knowledge and reflection, and to hope that thereafter, the right choices can be made.

I’ve tried to take a balanced objective approach rather than what I often notice – a tendency to bash the Regulator in order to enhance someone else’s different agenda or narrative, or a tendency to play the man rather than the topic.

Much gets written about the NHA ranging from very constructive to malicious. Sometimes opinions are based on mis-information, sometimes from not having any information, sometimes caused by the unwillingness of the NHA to enter a debate or even not being allowed to comment for legal reasons.

I hope that this article, covering a 20 year period from the transition of the Jockey Club to the NHA in 2004 to today, will be seen as a contribution to understanding perspective a little better.

I could write a book, but I will try not to ! Unless a Part 3, 4 and 5 become necessary!…(keep counting).

All of us who love this game should have but one purpose – to make it better and those who take the trouble to comment will I hope, have the intention to do so.

This is the NHA Head Office Boardroom where vigorous debate takes place, rules are made and enforced, appeals are heard, justice dispensed, and more than a few bloody noses occur. It’s probably the most important room in SA horseracing! (Pic – Supplied)

Part 1 Quick Summary

In Part 1, we learned that the forerunner to the NHA was the Jockey Club which had been in charge of the regulation and the Sport of horseracing for almost 150 years, and then found itself largely blindsided in the establishment of the public company Phumelela in consultation with the Gauteng Provincial Government between 1996 and 1998.

After the Turf Clubs in Gauteng, Free State and East Cape voted to assign their assets in exchange for 38% of their shares into the ownership of the public company Phumelela, the Jockey Club’s Board was in a quandary in regard the status of future control and regulation of racing and who would pay for it.

In 1998, Phumelela had that the Jockey Club take over additional responsibility of all officials that had previously been employed by each Turf Club, that is, handicappers, starters, handlers, judges and clerks of scale. It was logical, but would prove costly in swelling staff numbers to over 200, with more than 100 permanent staff.

Phumelela had also required that in order to help the public company to be viable, the Jockey Club would have to give up 2/3rds of its independent income derived from the tote turnover, whilst at the same time adding employment of the extra staff.

This meant that in the space of 12 months, the Jockey Club’s coffers went from R8,1 million surplus to R4m deficit. With annual deficits then running at R4m to R5m per annum, the Jockey Club’s reserves held in a Development Fund were quickly wiped out.

Clearly, a new funding system was needed.

One way – it was proposed and instantly rejected – would be to have the 6,000 rank and file licensees cover the deficit by charging a levy of up to R1000 annually per member and by also increasing registration costs every year.

“On what basis” asked certain Board members, “would owners, trainers, jockeys and breeders be personally happy to subside regulation so as to increase the profits of a public company!”

Constitutional Changes

All the same, on 6 September 2000, the Jockey Club sought to modernise itself to become more representative of the sport as a whole and at a Special General Meeting voted in favour to amend its membership from privileged self-elected classes drawn only from Turf Club Stewards who had a knowledge of how to make and apply Rules, to rather have the wider spectrum of granting all owners, trainers and jockeys and breeders an automatic subscription free membership and an entitlement to vote.

This seemed more democratic and egalitarian, though some argued that it was not appropriate because ‘Clubs’ have members, Regulators have Regulatees and allowing a popular vote against the need for strict, if unpopular Rules, was likely to lead to clashes.

And so it has turned out to be.

The critical role of the Regulator and the looming funding crisis

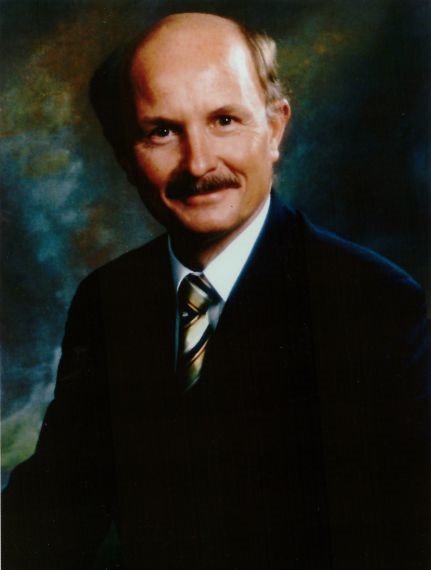

Saddled with a system in which the Public company Phumelela’s profits could be increased by reducing the funding to the Regulators, the 2001 incoming Chairman Alick Costa, attempted to address the prickly funding crisis in his Chairman’s address in the Annual Report.

Alick Costa

He carefully explaining the critical role of the Jockey Club to stringently enforce the Rules of Racing and Breeding fairly in order to protect the integrity of the Sport, which depended on the TRUST of public money.

He noted the now full time staff of 100+ full time employees plus a further 100 part time staff that comprised officials at racemeetings country wide for 364 days of the year, the 5000+ dope tests taken annually and analysed, the more than 120 disciplinary enquiries held so as to ensure the sanctity of results of races, eliminating cheaters, whilst also micro-chipping and DNA blood testing every foal born so that registration guaranteed the correct identities of the horses which raced, plus guaranteed the integrity of the Stud Book, around which the bloodstock market functioned.

It is a huge process, greater than most people realise or appreciate.

In noting the now revised funding system by the Racing Operators, he noted that the tote turnover had also dropped in recent years as the Operators moved into bookmaking and that Tote co-mingling with overseas countries did not increase turnover from which the Regulator might receive a percentage, because that the offshore tote proceeds were rather reflected as “income from Intellectual Property fees” in the Phumelela accounts.

As a consequence, the Jockey Club staff had not had any increase in real revenue above the rate of inflation for the past 8 years.

Costa suggested that a mechanism be found for a contribution from the bookmakers to be made directly to the Regulator pointing out that in 2000 bookmaking on racing had grown to 40% of betting whilst the Tote still enjoyed 60% and that an imbalance in which only the Tote funded the Regulator was, he wrote, “illogical, unreasonable and unacceptable”.

“Winning Bookmaking bets” he noted “also relied on the integrity of race results as guaranteed by the Regulator’s watchdogs and dope testing”.

“It is however” he wrote, “not a matter between The Jockey Club and Bookmakers, but between the Racing Operators and the organisations that licence bookmakers.”

“It is thus the responsibility of the racing operators to interact with the various Gambling Boards to ensure that bookmakers make a fair total contribution to the cost of regulation.”

Phumelela’s annual accounts meantime reported the income they received from the 3% Bookmaker’s levy to be R61m in 2001 and R44m in 2002. In those two years, the amounts they paid to the Jockey Club for regulation was R13m and R11m.

It seemed that relying on the Operators to negotiate a better dispensation on behalf of the Regulator was not going to work!

Phumelela had expanded into bookmaking themselves, setting up Betting World to become the second largest bookmaking exchange and they were not about to negotiate with themselves to give away profits from their bookmaking division to the Regulator.

In addition, Phumelela wanted to charge all other bookmakers a product fee, that is, a percentage of 1,5% of their betting turnover on horse racing in exchange for receiving the television picture through Tellytrack, and on which punters watched the races that they bet on.

Phumelela considered the 3% tax received from winning punters on horseracing and collected by bookmakers to be recompense for ‘putting on the show.’

Therefore they would not commit to anything more than an annual negotiation of the fees to be paid to the Regulator for ‘services rendered’.

This solved nothing for the Jockey Club.

The Philosophy of Regulation and the Law

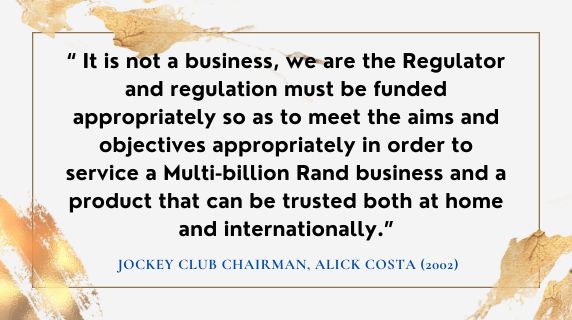

In the 2002 Annual Report Chairman Alick Costa explained the rationale and philosophy of regulation and the necessity of appropriate funding free from conflict of interest.

As senior partner at Werksmans Corporate Attorneys, Costa’s wise words remain true twenty years later.. I repeat his words here because it is important to understand the relationship of the Rules of Racing to the Laws of the country:

The NHA as a Self Regulatory Body

It is also important to understand that when a person decides to apply for the privilege of participating as a colour holder or registration as a breeder, or license as a trainer or a jockey or any other participant in racing, that person agrees to be bound by the Rules of Racing as defined and enforced by the Jockey Club (or NHA as is the case nowadays).

It works within the framework of the Laws of South Africa but on the basis that those who hold privileges agree to be bound by the Rules and accept the decisions made through enforcement.

At the same time, the paramount consideration is the PUBLIC interest and not the PRIVATE interest of individuals in racing, or even organisations licensed to be in racing. All are meant to be subjected to the Rules which are determined and overseen by the Regulator.

The Principle of Funding the Regulator

Chairman Alick Costa addressed this principle in the 2002 Annual Report where he weighed up arguments for and against the Regulator to be funded by the Racing Operators or by the State:

“There is a clear conflict of interest and duty which makes it undesirable for the Jockey Club to continue to be funded by the Racing Operators” he began.

On the one hand, the Racing Operators [who in terms of the Rules are annually licensed by the Regulator and pay a fee] accept and encourage that the Jockey Club must be well funded, that its staff must be properly remunerated and motivated so as to ensure that it is able to discharge its duties and responsibilities in an efficient and effective manner.

Also that the Jockey Club must retain its INDEPENDENCE – because the very existence of the Racing Operators depends upon their customers having confidence in the integrity of racing – and therefore in the Jockey Club”

“On the other hand, the Racing Operators are, inter alia, driven by profit motives and the interests of owners. This must inevitably encourage the operators to reduce the costs of operating the Jockey Club and specifically it’s staff costs, the major portion of our expenses, and thereby increasing its profits. There is thus a very real danger of the Operators undermining the effectiveness and independence of the Jockey Club.”

The Jockey Club should not be answerable, nor should it have to account to anybody but its members.

Regrettably, in real life, the old adage of ‘he who pays the piper, calls the tune’ tends to be true.

We accept this adage may also apply if the Jockey Cub is funded by the State.

The opponents of ‘State Funding’ say that they fear that this would be the case and that the perception of undue influence by the Racing Operators in the affairs of the NHA is unfounded and that State interference would be more of a burden. Lastly they say that it is preferable to deal with the Racing Operators who understand racing.

A decision was taken by the National Board to engage in discussions with representatives of various Provincial Gambling Boards regarding a potential new dispensation where the Jockey Club might be licensed by them and to discuss various issues including the collection and imposition of taxes.. which might be collected by the Gambling Boards and in turn would be paid over to the Jockey Club.

Depending on the outcome of these discussions, the National Board of the Jockey Club would then draft a proposal for a Special General Meeting of Members to consider (a direct relationship with the State).”

Birth of the NHA

No such SGM ever took place, the 3 year term of office of Mr Costa came to an end and the incoming Chairman of 2004, Peter Jaeger took the view not to pursue the State funding route.

Mr Jaeger was a racing man of many years, and had been a co-signatory of the 1997 MOU, the contract with the Gauteng Provincial Government that had given birth to Phumelela.

In 2004, under his direction, the Jockey Club changed its name to the National Horseracing Authority of Southern Africa, ascribing these reasons:

- The old name did not describe its functions

- Jockey ‘Club’ conveyed an elitist image from a colonial past

- Most people involved in racing, including punters, had no understanding of the role and functions of the Jockey Club

- It might have been the only independent regulator in the world still using the name ‘Jockey Club’

The new National Board would now comprise 7 members from the various provinces ELECTED by the membership, plus the CEO, and that for the first time, the regulatees would have seats on the board: the two Racing Operators and Racing Association and TBA would have the right to APPOINT a representative each.

At that point, Phumelela was growing profitably and well, KZN and Cape Racing had combined to become Gold Circle, Tellytrack had been set up to beam the South African picture across the world and foreign income was being generated from co-mingling.

Phumelela had been the first operator to set up betting on Soccer pools, and racing’s future looked bright. The NHA was determined to support the process in the greater interests of the Sport.

However, the conflicted position that the Racing Operators had a direct incentive to increase profits by reducing funding to the NHA, continued.

Efforts to reduce costs

In order to offset deficits of R5,5m in 2002 and R1,5m in 2003, the NHA was obliged to take steps to reduce costs in 2004:

- They wound down the NHA Staff Pension Plan in exchange for the salary increase. At least four employees refused, but all employer contributions to the Jockey Club of South Africa (1974) Staff Pension Fund ceased. By 2010 it was placed in liquidation.

- The Human Resources Officer resigned and a decision was made to save money by not replacing her, despite the staff profile of 99 full time employees and more than 100 part time employees.

- The IT division was closed and outsourced to the Racing Bureau at Gold Circle. This meant that the race results and statistics would no longer be compiled by the NHA. The leather bound volumes of results, the Racing Calendar, published annually as a record of all races since 1892, was ceased, as was the publication of the General Stud Book, published every 4 years and whose first edition was in 1899 and last edition, Volume 27 appeared in 2000.

- The NHA accounting functions were outsourced to Phumelela in 2007 to reduce costs.

- Stipendiary Stewards no longer had access to pool cars in order to attend race-meetings, rather having to use their own personal vehicles for track attendance, races and stable inspections.

- The Benevolent Fund which had been set up in the 1940’s to care for jockeys and trainers who had fallen on hard times after retirement, and had been funded by fines from those infringing the Rules, was closed down.

In 2005, there was a concerted effort by the Racing Operators to expunge the NHA altogether, with a delegation approaching Government to request that the Racing Operators be permitted to regulate themselves. This was dismissed as betting operators cannot have oversight of themselves if public trust is to be maintained.

2014 and Chairmanship of Adv Altus Joubert

By 2014, according to the Annual Reports, the number of permanent staff had been reduced by 23%, from 100 to 78.

As a matter of interest, by 2023, the number of permanent staff had whittled down to 58.

Past Chairman Advocate Altus Joubert

From 2017 to 2023, the cost of running the NHA has barely moved averaging around R82m per annum, of which 70% are personnel costs.

An interesting ‘rule of thumb’ experiment for me was to take R82m in 2017 as the bench year and apply the annual CPI (inflation) index (running between 4% and 7% p.a.).

If salaries had increased in line with inflation, the total operating cost in 2023 would have been some 30%+ higher. What conclusion can I draw but that the effort to contain costs might be causing under-remuneration of staff to subsidise the Racing Operator’s bottom line? It needs further evaluation.

Back to the story in 2014 and the NHA Board under the Chairmanship of Adv Altus Joubert determined that it was simply wrong that longstanding staff should not be assisted to meet their retirement equitably and therefore resurrection of a Pension Fund was instituted notwithstanding the impact it would have on the Budget. Furthermore that for such a large staff complement should be afforded the protection and assistance of a qualified HR officer.

The ability to retain staff at market related forces had become problematic.

In 2014, the Chairman of Racing Control, the NHA’s Chief Stipe, accepted an offer to transfer to the Gulf state of Qatar and double his earnings.

Similarly experienced Stipes left for Macau, Singapore, Malaysia and Mauritius. KZN Chief Stipe Sean Parker was headhunted to become Head of Stewarding for the British Horseracing Authority before he could even accede to the highest office in South Africa.

Adv Joubert’s increased budgetary move put him on the collision course with Phumelela who then refused to sign off the budget and consequently for a 3 month period they decided to NOT pay the NHA… “he who pays the piper calls the tune”.. and prove who was Boss!

This crisis led to an arbitration which was headed by Adv Paul Pretorius, later to become famous in leading the investigation into state capture and corruption in the Zondo Commission.

Adv Pretorius stated that a Regulator has the duty to regulate and govern independently and the Board should not include appointed representatives from the organisations that are Regulatees, lest they contribute to undue influence in their own favour. It definitely constituted a conflict of interest.

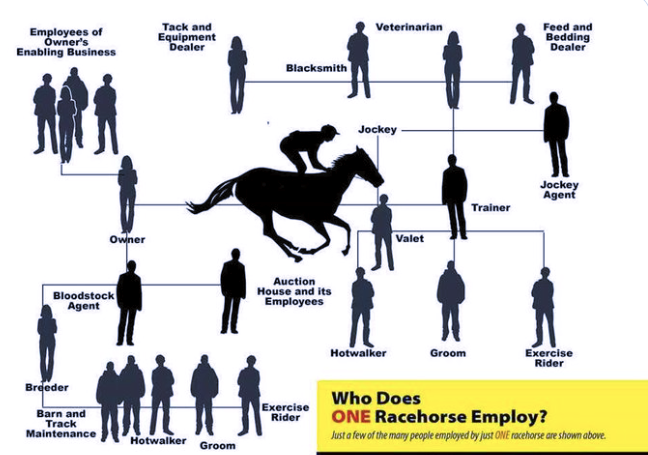

He noted that the National Horseracing Authority is the only National organisation in racing, that it has responsibility for the Rules and Laws which govern the livelihoods of 6,000 registered participants, who themselves employ a further 17,000 workers and that it was required of the organisation to be adequately paid in order to function correctly.

Advocate Joubert’s term of office came to an abrupt end when he was voted off the board in 2015 when his 3 year rotational term of office required that he participate in an election.

The vote was marred by an extraordinary incident in which the marketing department of Phumelela was contacting members of the NHA asking them to vote for the opposing candidate as “their preferred candidate” using a contact list that they had allegedly obtained from the RA – and as a result, the Chairmanship changed.

Settlement Negotiations

In the settlement negotiations that followed, the Racing Operators, RA and TBA stood down from the NHA board and it was agreed that an election system was no longer preferable and rather that a Nominations Committee of former Chairman should recommend suitable experienced independent individuals to serve on the Board.

The Racing Operators also wanted the NHA to sign an ‘employment contract’ agreeing to provide certain services against a Service Level Agreement and to submit the NHA to a clause which would enable the NHA to be dismissed if its services were deemed less than satisfactory by the Operators.

Such a notion would breach the Constitution of the NHA because a body that REGULATES not only determines the Rules and enforces them, but also GOVERNS as the ultimate AUTHORITY in the racing and breeding industries.

Legal Status of the NHA

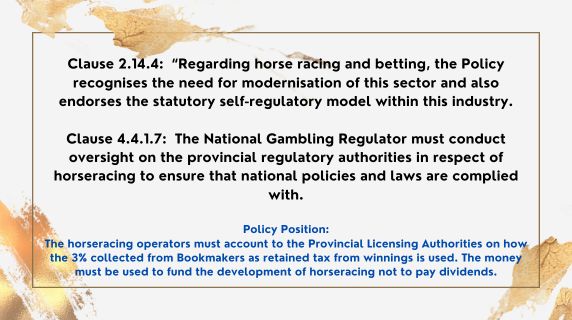

In November 2015, the DTI’s National Gambling Policy was published and stated the following:

Then in 2019, the Public Protector of South Africa conducted an investigation into Phumelela’s set up and made this finding:

- “Clause xxvi (j): There is an anomaly with regard to the funding of the operations of the National Horseracing Authority as the Regulator being funded by Phumelela, one of the industry players, thus compromising the independence of the Regulator”

And ordered this remedial action:

- “Clause xxix (dd): That the statutory body that is appointed as the Regulator of thoroughbred horseracing in the Republic must be capacitated to enable it to perform to its functions independently and without fear, favour or prejudice”

- “Clause xxix (ee): Ensure that the 50% Bookmakers levy which is paid to Phumelela by the Gauteng Gambling Board is withdrawn and transferred to the entity which will service as the Regulator for its operations as well as the development and transformation of the horseracing industry and also assist in looking into a new beneficial funding model”

As a consequence, the GPG did withdraw the payment of the 3% to Phumelela on the grounds that taxes collected for industry development funds should not end up in the pockets of public company shareholders, many of them individuals.

In other provinces, the cases were different: Gold Circle, for example, ploughed all of their 3% receipts into the development of the sport, transformation and public benefit causes, including their contribution to Regulation.

Phumelela subsequently took the Public Protector to court on review and succeeded in having the whole enquiry overturned.

However the Gauteng Provincial Government did not restore the 3% payments to Phumelela.

In 2020 the bankruptcy and collapse of Phumelela and the rearrangement and sale of Phumelela assets to 4Racing Pty Ltd in 2022 have prevented any decision on the 3% collections and have not paid over anything to any organisation in horse racing.

It is evident that given the above history, it is only the National Horseracing Authority as the Regulator that could successfully apply for the allocation of the 3% funds because the regulatory authority is the appropriate custodian of public funds to be used in the public interest.

It seems a logical process, especially given the legal authority accorded to the NHA by the National Government’s Policy decision 2015, above.

The NHA and their Authority in the Control of Racing

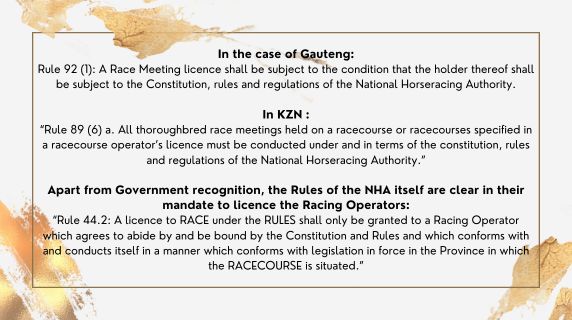

If the National Gambling Board under the DTI sees the NHA as the statutory regulator as a national policy, so too is this then mirrored in the Gauteng Gambling Board’s (GGB) regulations and the KZN regulations, below:

Conclusion

It’s pretty clear to me then that the NHA enjoys a form of Statutory recognition from both National and Provincial Government and is the TRUSTED Regulator, duty bound to ensure integrity of public monies and the fairness of results of races for participants and punters alike.

The means by which they should be appropriately funded remain slightly adrift, although in my view, there is substantial funding collected by the bookmakers in the 6% deduction from Punters Winnings.

According to the Statistics released by the National Gambling Board for the year ended 31 March 2023, the total aggregate bet with bookmakers on horse racing nationally in South Africa was R9,74 billion and the 6% winning punters tax collected appears to total R338 million.

The principle originally set up was that HALF of this (e.g. 3% or R169m) is accorded to the provincial fiscus’s and the other half (3% or R169m) is supposed to go to the horseracing industry or cater for its development, its health and for transformation.

Since 2019, the Gauteng portion has been withheld and some other provinces (e.g. KZN) have begun doing the same.

It seems to me, looking in from the outside, that if we have learnt anything from the past, the National Horseracing Authority would be firm favourites in any race to ensure that such R169m finds its way back to development and transformation of the Sport of horse racing.

Final Statistic

I will finish for now on one compelling statistic which arose from the Economic Impact Study orchestrated by Peter Gibson of Racing South Africa, and conducted by UCT a few years back.

They found that for every Rand gambled, the horse racing industry employs 23 times as many people as the any other form of gambling.

Our racing, breeding and gambling industries are a job multiplier – one job for every two horses – and we have the opportunity to enrich the lives of so many people and their families if we can become UNITED in our approach, ensure we get our new structures right, and fix the conflicts, anomalies and conflicts of interest of the past – it’s a worthy and noble goal.

The chart below reminds us that our central pivot is the HORSE, around whom all of our great sport and enterprise depend:

Note: Objects of the NHA – extract from the Constitution: