Trying to figure out ‘the problems’ in racing is exhausting. It is also an exercise in willpower and trying to wait until a respectable hour before heading to the drinks cabinet!

Of course, like most things, there is not only one nice, neat problem that can be easily solved with one nice, neat solution and trying to keep racing viable and profitable while keeping all the stakeholders (and now shareholders) happy, is like trying to herd cats.

However, as we’re all hard of learning, it seems we try anyway. We pontificate as to what we think ‘the problems’ are and what we think ‘the solutions’ must be. Surely they must be simple, and surely the people in the ivory towers are ill-informed, out of touch buffoons? Right?

The trouble is that first bit. That nothing is as simple as it seems on the surface, every proffered ‘solution’ teeters on a knife-edge that might set off a cascade of a gazillion other ‘simple’ sub problems.

What’s really going on?

I don’t know exactly how, or why, we got from ‘there’ to ‘here’. Reading back through racing literature, there seems to be a common thread of doom and gloom whether you’re reading contemporary articles, or stuff written 10, 20 or 30 years ago (or even further, if your library stretches that far).

So we are left with 2 possibilities. Either everything is just fine and the critics are eternal pessimistic doom and gloom mongers, or racing has somehow eternally teetered (successfully) just the right side of self-destruction. I’m not sure which is most accurate.

Being A Critic

I get a lot of flak for being critical. And that’s fair enough, because I AM critical (it more or less goes with the job description), but the point is that my criticism comes from a good place. Racing may be far from perfect, but at its best, when trainers mould and sculpt their charges like Michaelangelo’s marbles, and jockeys ride with instinct and artistry, and all the other bits that are supposed to work all fall into place and allow our horses to compete at their glorious, unbridled best, there is little as exhilarating and absorbing as a day at the races. The problem is that it can’t always be a Stubbs or Munnings tableau of perfection. And on the days that it isn’t, well, it grates and chafes like sand in uncomfortable places. And so I get irritable and tetchy, mainly because I believe that we are all a lot better than that and with just a small amount of effort (or lack of it), we can swing the balance either way.

It also doesn’t help that when I write about foals and rainbows and happy stories no-one reads the stuff and the minute I get my broom and pointy hat out, my articles go viral. So it seems that somehow we actually WANT to be irritated.

Perhaps I’m delusional, but it seems that with every passing day, the waves of ordinary chip away at what I believe to be extraordinary. And I can’t help but have a deep-seated belief that as long as someone keeps complaining and irritating, things might not slip. Or will perhaps slip a little more slowly. However, in those deep, dark, late night hours, one also starts to wonder whether on life’s great cosmic beach, you are the bikini or the chafing sand and which is the lesser of the two evils.

The Mechanics

There is an expression that genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration. Of course, we would all like the inspiration / perspiration levels to be a little more balanced. Or preferably reversed. Or, better yet, have someone else do the 99% bit. Because why SHOULD good ideas be such hard work, right?

Everyone wants to be there for the big bang, but no one wants to do the measuring and the weighing and the careful laying out of the fuse lines and the safety checks and making sure that it’s all done correctly and at a safe distance. And so we get caught in the middle of all the good intentions, with no-one really doing anything and everything ends up feeling a little, well, unsatisfactory. Unfortunately without all the careful quantifiable weighing of decisions, actions and consequences (it’s a word – look it up), we are left in a constant stew, caught between magic, mayhem and mud.

Here’s to sand

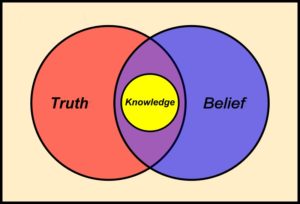

In his excellent letter to the editor of the TDN, Sam Ferguson wrote “The success of racing isn’t about race day medications, or federal regulations with the U.S. Yada-Yada whatever watching over us. It’s about people, fans, bettors, interested in an emotional endeavour, a racehorse bound with unsurpassed beauty, power, and spirit trying to win a race. People, probably dulled through their daily grind of an existence, seek something interesting and entertaining. Sports don’t attract people with corrupt business practices, shady dealings, drugs shot up into innocent horses, or even gimmicks. Sports attract people with knowledge, which leads to understanding.”

He’s got a point, because once you understand something, you learn to trust it and to love it. Unfortunately we stubbornly refuse to use knowledge to attract people.

I don’t know about most of you, but what I’ve learned in my 40-odd years on the planet is that growing up is vastly overrated. And most if it is rubbish anyway. Most of what I need to get through life, I learned in my first few years of pre-school. Honesty, integrity and above all, consistency. As a bit of fun, I found some definitions of integrity. One describes it as the “quality of being honest and having strong moral principles’. Another ‘the state of being whole and undivided’.

Has she gotten to the point yet?

Nearly there, I promise. I believe that a solid regulatory body is the cornerstone of any organisation. It’s a little like the Dewey Decimal System is to a library. Without some basic rules and order, it doesn’t work. No matter how elaborate or exciting the contents.

So, I’ve been sitting and watching our NHA at work over the last few months, perhaps longer. And as the guardians of our ‘library’ as it were, wondering whether I’d enjoy or make sense of their particular system of managing racing. At this point, I must confess I’m not convinced.

I’ve had a fair few excuses to deal with the NHA and I find them, in turns, exemplary and strangely bewildering. Lists are good for figuring things out, so I made a list of the most recent inquiries and appeals to try and make sense of it all and I seem to have finished worse off than when I started. No two cases seem to be the same, no two penalties seem to be the same, some incidents are blown out of all proportion and, judging by some of the chat sites, some are overlooked entirely. Some of it may be justified, some of it may be the NHA trying to justify its existence and some of it may just be plain bad decision-making. I’m not sure.

Regulating the Regulator

Now I can hear my ‘fan club’ going ‘oh, she’s being a bitter old so-and-so’ and just picking on the poor old NHA again. Well, yes, but I’m whinging with intent. I believe we need a strong and autonomous regulatory body and I believe that we can do a lot better than we are at the moment. There are a number of different reasons for that, but the main one is money. The second is belief.

Let’s deal with money first. It is clear that the NHA is funded, by and large, by the Operators. It has also become patently clear that times are hard and that budgets are a lot slimmer than they once were. Stemming from the current government interest into our gambling policies, they are looking at our regulatory function and tinkering with the wording of various legislation. Rumours abound of plans to ‘unpack’ the NHA and distribute its functions to existing racing structures.

Of course it is reasonable for the Operators to scrutinise costs – including the NHA – evaluating whether they offer value and acting accordingly. But what price integrity? While times are hard and economising is sensible (apart from the hospitality budget apparently), it is possible to rationalise the life and soul out of something and I suspect we may have crossed a line. Our regulatory body is, after all, what gives us shape and form and function. It is what we all set our clocks and stand and fall by. We should be building it up, not breaking it down.

You Gotta Have Faith

Moving on to the ‘belief’ part, no system can work without a certain amount of faith being vested in it. It is also not a static structure, but a living, breathing organism that can, or at least should, be able to react organically to its environment – within prescribed limits of course. This means investing in the process, believing in it, but above all, contributing to it. It also, unfortunately, means abiding by it. No short cuts or special treatments for selected people – or draconian punishments either. I’m not saying wrong-doers shouldn’t be brought to book, but unfortunately, when you start playing fast and loose with the rules, well, you’re playing a dangerous game. Systems take months, years, even decades to develop. Successful systems sometimes longer.

Without a robust system, we have no grounds on which to build trust. In an industry built on chance and myth and legend, without trust, we have nothing. So does the fault lie with the rules? The interpretation of the rules? The application of the rules? The people enforcing the rules? Or is it perhaps even further up the food chain with the people financing the thing? I suspect there’s more than one correct answer here.

Overpaying / Underpaying

I recently came across a gem from David Halberstam’s book, The Breaks of the Game. In 1974 the Pittsburgh Steelers drafted Lynn Swann. Swann was the twenty-first choice in the draft but his agent, Howard Slusher, managed to negotiate for his client the second-highest starting salary of that year’s rookies. In simple terms, Slusher managed to get Swann paid like a two instead of a twenty-one, a pretty rare feat. At the press conference to announce the signing, Slusher was pulled aside by Art Rooney, the owner of the Steelers, who said “You think you screwed us, don’t you?” Slusher took the politic route and didn’t respond, although privately he did think he had gotten the best of the Steelers. “You’re wrong,” Rooney responded. “We got you. My son says he’s not a good football player, he’s a great football player. Probably the best draft pick we’ve ever had. Maybe better than Terry Bradshaw or Joe Greene.” (Since Swann went on to have a Hall Of Fame career, Rooney was dead on about “great”). Slusher could tell Rooney wasn’t done making his point so he didn’t respond. “Let me teach you a lesson, young man,” Rooney said. “You can never overpay a good player. You can only overpay a bad one.” And he was right. Great employees are worth significantly more — to teams, to customers, and to the bottom line – than average or even above-average employees. Sometimes twice as much. Sometimes multiples more. So forget scales and benchmarks. Truly top performers are rare. Pay your superstars not just as if you want to keep them… but as if you desperately need to keep them. Because you do.”

Final thoughts

An industry authority on regulatory matters recently made the comment that what we need is not just consistency, but consistently good decisions. I think we need a superstar NHA.

Perhaps, as Winston Churchill once said, once we’ve exhausted all other possibilities, we might do the right thing.