The National Horseracing Authority’s founding and relationship with the now defunct Phumelela goes to the heart of its measures of control.

Opening Page of the NHA’s Annual Report

From 2006 to 2015 and again from 2018 to 2021, I served as an elected member on the Board of the NHA, writes Robin Bruss. Because of this 14 year experience, I feel qualified to make some comments and observations.

These are my own independent views as I’m no longer on the NHA board or any other board in horseracing, and all facts below are in the public domain from which I derive my views.

I was an elected member of the Board, as distinct from an appointed member representing one of racing’s organisations, such as the TBA, the RA or the Operators.

To be elected to serve on such a board is an honorary position in which one vows to uphold the Vision and Mission of the NHA, instil and enforce the Rules of Racing and protect the sport from malpractice.

Those 14 years were tumultuous because they coincided with the rise and fall of the public company Phumelela as the owner of the racetracks and the largest betting operator for two thirds of South African horseracing.

Phumelela’s rise was steep, starting in 1998 to take over most of racing’s assets, given on a plate, to become a Listed for-profit company on the JSE in 2001, a steep rise in share price from 50c to R22, more than R1,3 billion in profits paid in dividends to shareholders before nosediving from grace and having to file for bankruptcy in 2020 when hopelessly insolvent.

Some History

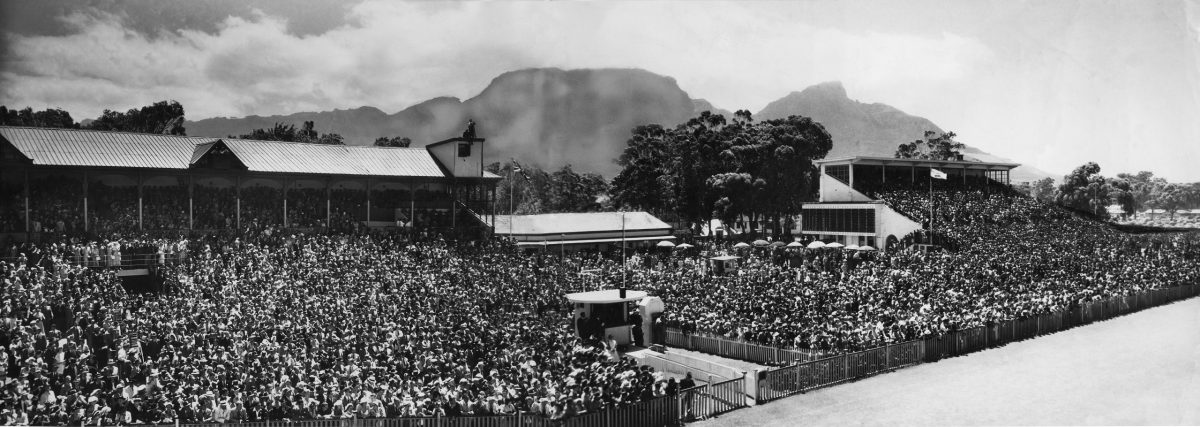

Horseracing had previously operated in South Africa for more than 150 years under a system in which the Jockey Club of South Africa was totally in charge.

They were the Government recognised and appointed non-profit Authority that worked in the public interest.

It regulated the Sport by providing Rules and enforcing them, it operated the Stud Book and registered every horse and provided identification and passports and checking to ensure that every horse that raced was the correct horse, it registered and licenced every participant, it had oversight of the integrity of the weights and conditions of races, it recorded and published all the results, it conducted dope testing, it had oversight of betting sheets, it licensed the Tote and the Bookmakers.

To be a member of the Jockey Club, which safeguarded public trust in a multi-billion Rand Sport, was a position of high esteem that carried respect and authority and prestige.

The Board was drawn from men of great weight and stature and they safeguarded the public trust fearlessly and diligently.

They provided the character, status and the moral compass for the development of a respected sport and an industry regarded in size and stature in the early 1990s as the third biggest in South Africa after mining and agriculture.

Horseracing had a monopoly on gambling

From 1948 to 1998, horseracing had a monopoly on all gambling in South Africa.

This was because it encompassed three industries:

- An Agricultural industry that bred horses all over South Africa and employed a large labour force in order to produce animals to race;

- A Sporting Industry operated by multiple Turf Clubs. The first Racing Calendar 1892, the annual hard bound book of race results produced by the Jockey Club, listed 36 different racetracks. When Phumelela started there were 14, now there are 7.

- A Gambling Industry which was betting on the outcomes of the races.

It was well organised, orderly, fiercely controlled by great Stipendiary Stewards like Jock Sproule and Frank McGrath, whose word was law and who enforced the Rule Book strictly and fairly.

Because they had oversight of betting, they could call for the betting sheets from bookmakers when results were awry to ensure no skulduggery was at play.

Its status was to be a self-regulator under the aegis of the Department of Trade & Industry, in whose ministerial portfolio, all gambling exists.

Independent Regulator

The Jockey Club’s funding was independent, drawn from 1.5% of the Tote Turnover and collected by the Turf Clubs and paid over.

Until 1998 the Tote was a colossus comprising 2/3rds of all gambling in South Africa. The Bookmakers were the other 1/3rd.

Casinos existed, but not in South Africa, they had been set up as revenue sources in the Bantustans, the homelands such as at Sun City in Bophuthatswana – which were to be integrated back into the new South Africa in 1994 and thereafter the monopoly was lost and horseracing had to compete against casinos and a new National Lottery. For this reason, 1995 to 1998 became watershed years for the setting up of a new corporatized model for horseracing – which gave birth to Phumelela.

The Jockey Club Reserve Development Fund, built up over many years as a prudent buffer to ensure financial stability held R20 million from which to run projects or develop or promote the Sport, upgrade lab equipment or run investigations.

The Turf Clubs which the Jockey Club licensed annually were each operated by a voluntary Board of Stewards, with oversight over a professional management team at each track.

The member elected Stewards of these Clubs ensured compliance with Jockey Club Rules and did their best to market racing as a social and collegiate sport as well as a betting enterprise attracting members who were both fans and participants in the Sport.

The Highveld Betting Act 1965 allowed for 5% levy on off course tote turnover to create a Provincial Development Fund with a separate board which would permit allocations to the Turf Clubs for particular development projects – such as new stabling, grandstand updates, contributions to the Jockey Academy, Totalisator upgrades, grooms quarters and so on.

All of this was the working system of an independently funded Regulatory body in charge with no conflict of interest. So far so good.

This all changed when the new For-Profit model of Phumelela arrived in 1998.

The Phumelela model

This model was initiated by the Gauteng Provincial Government in 1995 in the knowledge that the Casinos propping up the ‘homelands’ would be integrated into SA as the new South Africa came into being.

The National Gambling Act was in the process of being re-written Version 1 in 1996, updated in 2004 and again in 2008.

At that time, in 1995, it was believed that corporatisation was forced upon the racing industry by edict by the Gauteng Provincial Government, but in 2019 at an inquiry by the Public Protector’s office, it became apparent that certain of the operators had been consulting and making recommendations on corporatisation to the GPG without the knowledge of the Jockey Club.

In fact, the Jockey Club had itself proactively commissioned studies by Standard Chartered Bank and Deloitte & Touche as far back as 1991 and an independent enquiry appointed by the State President, the Howard Commission, had also investigated and made recommendations on the gambling industry post 1994, and all of these studies recommended against a corporatized model for horseracing.

At the 2019 Public Protector hearings, ex GPG Finance Minister Moloketi was deposed and denied having been provided with any of the Jockey Club documents or the Howard Commission and insisted that the corporatized model was the one that racing wanted.

He stated that the GPG liked the model because the GPG would permit the corporatized public company to be assigned all of the assets of the Turf Clubs effectively for free on a vote by the members of the Turf Club, and in return a new body, a non-profit Racing Association (comprising Turf Club members and members of the Owners & Trainers Association) dedicated to the Sport of horse racing would be allocated 38% of the shares of the public company and a further 25% would be allocated free of charge to Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) shareholders, the balance would be floated on the Stock Exchange.

The new company would be known as Phumelela, a zulu/xhosa word meaning ‘to succeed’.

The Racing Association was founded for the purpose of receiving dividends of 38% of Phumelela profits.

Their shares had to be held by a Trust – the Racing Trust – and the Trust and the RA’s main purpose was an important role, to protect the ethos of the sport and be a watchdog in the protection of excess by Phumelela, protection of the stakes agreement to ensure that the public company could not increase shareholder profits by cannibalising assets, such as selling off racetracks to boost profits, and decreasing provision of stakes and services in order to boost their own profits. It would use its share of dividends to promote the sport.

These roles above effectively side-lined the authority of the Jockey Club.

Bookmaker licenses and oversight on gambling were allocated in 1998 to the newly formed Provincial Gambling Boards who would also allocate new casino licenses, slots, bingo and other forms of wagering and betting.

Gambling was about to explode and horseracing would face increased competition.

Whilst it looked like a good model initially, the Phumelela corporatisation was meant to safeguard the sport whilst allowing what public companies are meant to do – to use their powers to expand the business, grow profits and ride the wave of an explosive gambling industry for the benefit of all.

Phumelela’s bankruptcy lies at the foot of bad strategy. When they took control in 1998, total gambling aggregate was R8 billion. By 2020 when they went insolvent, the national gambling aggregate was R451 billion, a staggering growth of 5,300%. Effectively the industry was growing at between 25% and 40% per annum and on this huge wave, Phumelela somehow had focused on racing’s internal assets and not grown the company into the gambling colossus that other betting enterprises like Hollywoodbets and World Sports Betting have become.

Phumelela’s short story

In the voting of the assets of the Turf Clubs to be assigned for free into the new corporation, one of the inducements stated on the voting paper was that the Gauteng Gambling Board would make a provision for 6% to be deducted from punters winnings on horseracing.

Half of this would go to government taxes and half (3%) would be allocated to the horseracing industry.

This was a way for the bookmaking industry to help horseracing. It met with significant approval by turf club members on the assumption that this would run into more than R50m per annum of new income to the sport.

The vote for Phumelela receipt of the Turf Clubs assets in Gauteng was 99%.

However, in the final contract signed by the founders of Phumelela and the GPG, it was determined that there was no such thing as a ‘horseracing industry’ bank account and that the word industry should be replaced with the word ‘Company’, allowing Phumelela to receive the 3% flow and that they would undertake to be responsible for the horseracing development.

This was recognised by the Public Protector in 2019 as a clear conflict of interest and their investigation showed that the lion’s share of the flow of the 3% found its way into the dividends declared to shareholders and therefore ended up in shareholder’s pockets. For this reason, they ruled in 2019 that it should no longer be paid.

The fact is that at the height of Phumelela’s annual profits in 2017, their Annual Report showed gross profit of R152 million, of which R74 million was reflected as income from the 3% and R50,6 million was from unclaimed dividends and fractionals from rounding down on Tote dividends, effectively public money, not company revenue.

In the proposed National Gambling Amendment Bill, it will be illegal to assign public funds so collected as income to the Operator.

If 82% of Phumelela’s income was from these sources, did this mean that their profits from running BETTING operations was puny ? And why would that be ? According to the National Gambling Board published statistics 2017, the bookmaker turnover grew spectacularly by 30,8% in the same year.

Under Phumelela’s watch the Tote turnover had declined by more than 50% despite being the initiator of sports betting in their soccer pools which also failed to take off and accounted for less than 1% of their income.

The NGB stats showed that Sports Betting with bookmakers was hugely popular and had rocketed, increasing from R854m to R62 billion turnover in the ten years 2009-2019 – a 72 fold increase.

If Phumelela had exhibited the 72 fold increase, racing would have hailed the model and funds would be flowing everywhere.

Somehow the strategy of Phumelela missed the mark completely.

Graph to show the increase of all bet types in R’billions, except the Tote in the

decade leading to Phumelela’s demise.

Phumelela and the Jockey Club

With the above as the background, we now come to the heart of the NHA’s story.

The Jockey Club’s intended role

In 1999, the Jockey Club Chairman, Matthew McElligott defined this in the Annual Report:

“The Jockey Club is a committed regulator seeking to regulate a complex sport and industry as effectively as is reasonably possible. Its regulatory function is essentially to determine the rules for racing and to provide the discipline and control necessary to enforce them. Integrity in racing is the key to racing’s’ survival and because of this, uncompromising but fair and firm discipline and control is absolutely essential to maintain the confidence of the public”.

Effect of the Changing Landscape on the Jockey Club/ NHA

In January 1998, Phumelela dispensed with the system of the Raceclubs having voluntary racemeeting stewards at the racetracks in order to reduce costs.

These Stewards had hitherto had two purposes :

- To supplement and support the Stipendiary Stewards in their integrity services during racing at the track, including sitting in on objections and hearings.

- To support the social fabric and prestige status of horseracing and the ethos of the sport. The purpose of disposing of them was to reduce the costs of Stewards Rooms

KZN and Western Cape had a different construct, but planned to merge into Gold Circle and also reduced the number of racemeeting stewards.

Chairman McElligott commented on the impact:

“In Gauteng, some dissatisfaction was expressed in regard to maintenance of discipline and control, exacerbated by some perhaps unjustified press comment. The problem may be one of poor communication and a solution may have to be improved liaison directly between the Stipendiary Board and Phumelela and the Racing Association”

In 1998, in order to reduce costs prior to its listing, newly formed Phumelela began transferring any staff related to administration and integrity services to the Jockey Club overhead.

Racemeeting officials were also transferred from now defunct Turf Clubs to the Jockey Club whose permanent staff swelled to 100 with more than 100 part time staff officiating country wide in 364 days of racing per annum.

Funding Structure changes in 1998-99

Negotiations took place in December 1998 which were to profoundly affect the Jockey Club in the future and this was reported in the Jockey Club Chairman’s Report:

“ In December 1998 we commenced discussions with the racing operators with a view to determining a revised approach for meeting the costs of operating the Jockey Club. With effect from 1st April 1999, the levy from the racing turnover of Phumelela was reduced from 1.5% to 0.55% of totalisator turnover, the reduction being entirely a reduction in the contribution to the Jockey Club Development Fund. From 1 July 1999, levies payable by all operators and Clubs were further reduced from 0,55% to 0.5% of totalisator turnover. Again the reduction of a further 0,05% reflected a decision to discontinue contributions to the Jockey Club Development Fund.”

The net effect of reducing the tote levy by 2/3rds and increasing employment caused the Jockey Club to go from an R8.1m profit to a record R4,5m loss in 1999.

To solve the need for cash flow, the entire balance of the Jockey Club Development Fund of R10,6 million was then transferred to the current account and the Jockey Club entered an era of a future without a safety net.

The Highveld Racing Development Fund might have helped but the GPG annulled the Betting Act of 1965 and the R80 million in the fund was allocated to Phumelela as a grant to cover their startup costs.

It almost certainly meant that on the day of listing the share price rocketed from 50 cents up to share value of R4.00.

The Jockey Club, arbiters and regulators for the industry, were left in the cold and the Phumelela era began.

There is little doubt that the 3% could been paid to the Jockey Club Development Fund. It could even have been paid to the Racing Trust, whose 13 objects were broad-based and industry focused.

Both were designed as industry bodies, although the Jockey Club was national and the Trust was provincial.

It’s also apparent now that it should have been legislated to preclude for-profit Phumelela shareholders or their nominees from being Trustees of the non-profit Racing Trust.

Serving on both boards at the same time was a clear conflict of interest, but it occurred.

The Laboratory and integrity of racing

The single most important function that the NHA has is to safeguard the bettors from doped horses and to ensure integrity of results.

Therefore the laboratory ranks as one of the best in the world for this purpose, comprising a staff of 15 persons and conducting more than 5,000 dope tests annually.

This is a sophisticated and costly exercise, but the lab scored 100% proficiency on international testing for the 30th consecutive year – a significant achievement. It is regularly used as a Reference lab by overseas jurisdictions.

In 1999, the Jockey Club Chairman’s Annual Report stated:

“It is important to note that the laboratory will, for the next 4 to 5 years, require an ongoing programme for replacement of equipment involving expenditure of approx. R1m per annum. In the past the levy on the Tote Turnover of the racing clubs was not expected to finance the purchase of laboratory equipment. Instead it was agreed that such equipment would be financed on an as required and agreed basis from capital contributions from the Racing Clubs, operators or the various Provincial Development Funds. Now that the Development Funds for the Provinces have been closed and handed over to Phumelela and Gold Circle it becomes necessary to hold discussions to agree an appropriate resolution.”

The Racing Trust was required in its objects to fund items of a capital nature for the Jockey Club/ NHA such as new lab equipment, but simply refused. The resolution was for the Jockey Club to take out a loan from Gold Circle and repay it over 5 years with interest.

The Jockey Club had set up the Jockeys Academy at Summerveld in 1961 and was obliged to continue funding it when the Racing Trust decided it would only fund provincial service in Gauteng.

Between 1999 and 2005, the Jockey Club Development Fund paid R11,6 million to the Academy depleting the whole fund which then folded.

After 45 years at the helm of the Jockeys Academy, the Jockey Club/NHA relinquished all control, although it still owns the title deeds on which the Academy sits.

The Parlous State of Finance in 2000

In 2000 the Chairman’s Annual Report opined the Jockey Club’s predicament and admitted that they were on the ropes:

“The spirit of the negotiations with the Racing Operators was to fund the Jockey Club’s operating and capital expenditure in terms of an approved budget. Regrettably the necessary funding on this basis was not forthcoming from the Racing Operators, so for the years 1999 and 2000, the Jockey Club has experienced losses in the region of R5million annually. If a similar shortfall were to occur this year, the ability to continue at all is doubtful.”

“What must be understood is that the funds will have to come from somewhere, whether the Racing Operators or other participants in the industry, as a matter of urgency, or racing at its current level of discipline and integrity will not be sustainable.”

In 2001, negotiations occurred between the Jockey Club and the Racing Operators (Phumelela and Gold Circle) who agreed to replace the low fixed percentage of turnover with an annual negotiated arrangement with the Operators.

However, the problem with this principle is that any increased regulatory cost would impact the Operator’s net profit, and accordingly, it became a disincentive for the Operators to pay more than cut-to-the-bone costs.

All of these financial and control matters must have weighed heavily on the Board of the Jockey Club back in 1999 and they had already started a review of their Constitution in preparation for a new dispensation which would need to be negotiated with Phumelela and the newly formed Gold Circle (which comprised KZN and Western Cape Racing) – and this new dispensation would re-branded in 2002 and called The National Horseracing Authority of Southern Africa.

Over the ensuing years, as will be explained in Part 2 of this article, the new dispensation was far from ideal as it caused nine consecutive years of budget cuts, NHA functions to be outsourced, staff to be under remunerated, their pension plan to be stalled, and as service quality slumped, a direct but unsuccessful challenge in 2005 by the operators to attempt to expunge the NHA altogether and usurp its functions.

Part 2 will follow next week and outlines the birth of the NHA model, its successes and its constraints, and why, after 20 years of struggle, it needs to change again, especially now that Phumelela is no more, and all of racing is busy re-inventing itself.