When looking at yearlings, or any horse for that matter, it is easy to be carried away by one or two special points, and forget about the rest, good or bad. Following the checklist method is a useful aid in lessening the odds against making an all too expensive mistake when shown up in that penetrating but often infuriating light of hindsight.

Catalogue check-list (table 1)

1. Class

2. Speed

3. Stamina

4. Performance at stud

5. Performance on the track

6. Soundness as racehorses

7. Well known character traits, temperament

8. Looks and prepotency

9. Age

10. Stud where bred

11. Likely cost bracket

12. Value for money

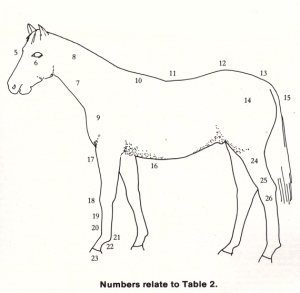

Physical checklist (table 2)

1. Balance from the side

2. Balance from the front

3. Balance from behind

4. Will it grow into a racehorse? High quarters?

5. Head (mouth, ears, shape)

6. Eyes (likely temperament)

7. Throat (unconstricted)

8. Neck and set of head (horse, not a camel)

9. Shoulder slope (and depth)

10. Withers (prominent enough)

11. The back (strength)

12. Loins (strong)

13. Croup (well shaped)

14. Quarters (deep strong hip giving way to well rounded muscular buttocks)

15. Tail (well set, not too high)

16. Depth of girth (plenty of heartroom)

17. Forearm (long, well fitting, strong enough)

18. Knees (well aligned, roomy, flat side-view)

19. Cannons (short, sturdy, not ‘tied in’)

20. Tendons (clean, easily seen)

21. Fetlocks (well shaped, in proportion)

22. Pasterns (length, slope)

23. Feet (shape size, care pair, walls, soles)

24. Hip-to-hock measurement (long)

25. Gaskins (long, strong, well-fitting)

26. Hock (line, angle, strength)

27. Walks (from behind, side-on, the stride)

28. Swellings, injuries (ask the vet)

29. Overall presence and balance on the move

30. A valuation in conjunction with the breeding

It goes without saying that prospective buyers, whether they are depending on their own judgement or that of their trainer, agent, veterinarian, or combination of all three, look at both breeding and conformation. All but the most experienced seek professional advice. Most people, but not all, first look through their catalogue. They may study all the sires represented and eliminate those they do not favour for reasons that may form a checklist in itself (see table 1). The same list applies with equal value to dams. Then there are those people who remember good characteristics: Soundness, courage, toughness. But a danger, even when studying breeding, is to be carried away by one promising feature only. The black type in the catalogue, for instance, indicates winning ability and is important, but is by no means the whole story.

Single, or one-track mindedness can also apply when looking at the yearlings in the flesh. It is easy to form a fixation (about hind legs, for instance) and look at little else. Hence the checklist. The one to be discussed here is a basis. It has room for addition. Obvious faults have been left off, curbs, swollen joints, wounds, bumps – those are the things that need consultation with a vet before the decision to bid is made. After all, the whole business of careful selection of yearlings is an effort to lessen the odds against failure, and in doing this increasing the odds of success.

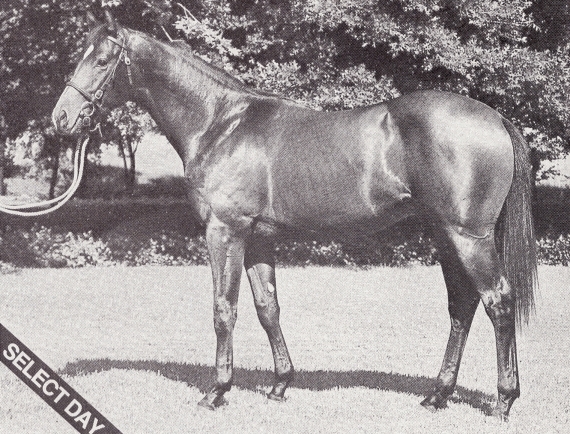

In looking at the overall conformation of a yearling, it is as well to remind oneself that it is real faults that one is seeking. Almost all horses can be faulted in some way, and some remarkably slow horses are hard to fault !

Judging Balance

A well-balanced horse will have everything: head, neck, shoulders, back, loins, croup, legs, joints and feet all in proportion. What proportion? Proportion to its height and length. What height and what length? Not too short certainly, and sometimes not too tall. Lengthy certainly, but the length should come in the neck and slope of the shoulder rather than the back. It is not hard to gauge proportion when looking at many yearlings at one time. Try, if you can, to see them at exercise. Some will look balanced and in proportion, others will not. Some will look balanced, but smaller than average. Others will look heavy and even fat. Some will have presence, others will look ordinary. There will be big heads, short necks, straight shoulders, long weak looking backs – when compared for balance with others all that shows up.

Comparisons with the best horses helps to train the eye. Balance of the parts is best seen side-on. A yearling must also be inspected from the front , not too narrow, not awkwardly wide. And from behind, so see that hips and quarters match, that the walk is smooth and even. No bandy legs.

Having been taken with the presence of the yearling, examined its balance from all angles, and pictured in the mind’s eye a future racehorse, stamped with quality and presence, the next step is to look at each point.

The Head

Start with the head and work back. A long heavy head will be out of place. The eye should be large and honest, alert, full of character. Both eyes should be seen – like everything that comes in pairs – there should be no sign of difference, no defects or cloudiness. The jaws should fit nicely, no underhung or parrot mouth to affect the function of the teeth. The ears should be comparatively small and alert. Concave or dished faces run in certain families and come originally from arab strains; they add a touch of class to the head. The neck should be wide enough to take the windpipe comfortably, not narrow or short, it should contribute to the length of rein. High class horses have a long rein from the back of the withers to the mouth. The set of the neck should be balanced, not giraffe or peacock-like, not hanging and heavy looking. Avoid on the whole the curved cresty looking neck such as a stallion develops.

Shoulder

The slope of the shoulder is important, and a guide to the length of the stride. The slope forward should be marked, and there should be depth to it. The withers joint the backbone to the neck, and should be high and sloping, strong, but not thick and not merely a bump. Below the shoulder and joining it to the elbow, the humerus should be vertical and long.

Heartroom

Ample “heartroom” is required: that is depth of girth behind the elbow. The yearling must not be massive, like a deep barrelled carthorse, but even that is better than no girth at all. Nor should there be a markedly upward slope towards the flank, giving a greyhound appearance, which may lighten up later into a “herring gutted” look. A likely sprinter may have a deep barrelled and even wide chest when seen from the front. The potential staying horse is altogether a lighter built animal. But most buyers will be looking for class and the high class miler or middle distance horse will seldom be a heavyweight, or a featherweight for that matter. A narrow horse with both front legs seeming to come out of the same hole is to be avoided.

The Back

The back should be strong, without tendency of dipping or concavity. It should not be too long, yet there should be room to take a long stride. This will be provided for in the slope of the shoulder and the depth of hind quarters. Strength must run on through the loins and croup, which should not slope away too much, or again the stride will be short. Many good stayers have not possessed a long stride, but for speed and class it is a prerequisite.

Legs

A horse, whatever faults or points of virtue it may have, needs sound legs and good feet to enable it to be made into an athlete capable of winning races. A minor fault or two may be found in many good, even great racehorses, but fetlocks, feet and knees have to take tremendous strain and chances can seldom be taken with them. A knee is intricately designed and therefore easily damaged.

The drive comes through the thighs, which should be powerful. The gaskins, or second thighs, should be strong, flat, well fitting, and as long as possible to the hocks. The lower the better the hocks for stride; the straighter the better for speed, which is not necessarily the same thing. The angle of the hock formed between gaskin and lower leg should not be too marked, nor too “far away”. The hocks should be neat and lean and, of course, a pair. The cannons between hock and fetlock should be short. This applies both front and back. The stride is in the long sloping shoulder, the humerus, the elbow and the forearm in front; and behind in the croup, the long femur or thigh bone, and the length of gaskin.

Fetlocks, or ankles should be small, angular, flat and tight; neat, and a perfect pair. The slope of the pasterns should be at forty-five degrees to the ground, or the shock absorbing is lost and the horse may jar itself or step shorter on firmer ground. Long pasterns can be a weakness, and with length the angle becomes important. Very short pasterns bring the fetlock close to the ground.

Knees must be looked at from in front and side-on. From the front the whole leg should be straight enough to carry the weight without deviation from a plumbline, running down the forearm through the centre of the knee and to the middle of the fetlock and foot. It is as well to stand in front and gauge this line: weight should be distributed, and never concentrated. Seen from the side, a knee should not curve in or out, but blend into the leg and be part of it. It should look flat. Back at the knee (or concave) is considered a serious fault for clear enough reasons: the knee is designed to face forward and flex backward, unlike that of for example a stork. Over at the knee is less serious, but extra strain in placed on the joint as soon as any part of the foreleg is out of position to take the tremendous shock measured in the momentum of the galloping horse.

Feet

The feet must be a pair. No good if they are narrow, or irregular. They should not turn out or in, be splay-footed or pigeon toed. When walking the feet should land squarely, the weight distributed evenly. Soles require expert inspection: they must not be thin, and heels should be wide.

Table 2 summarises all this in a handy checklist. A starting point for the uninitiated if you like. A method for not falling into the trap of short-sightedness. When you use it, try to see your yearlings in a place where there is space enough. After all, it’s your money!

Futher Reading: Natalie Keller Reinert blogs about yearlings