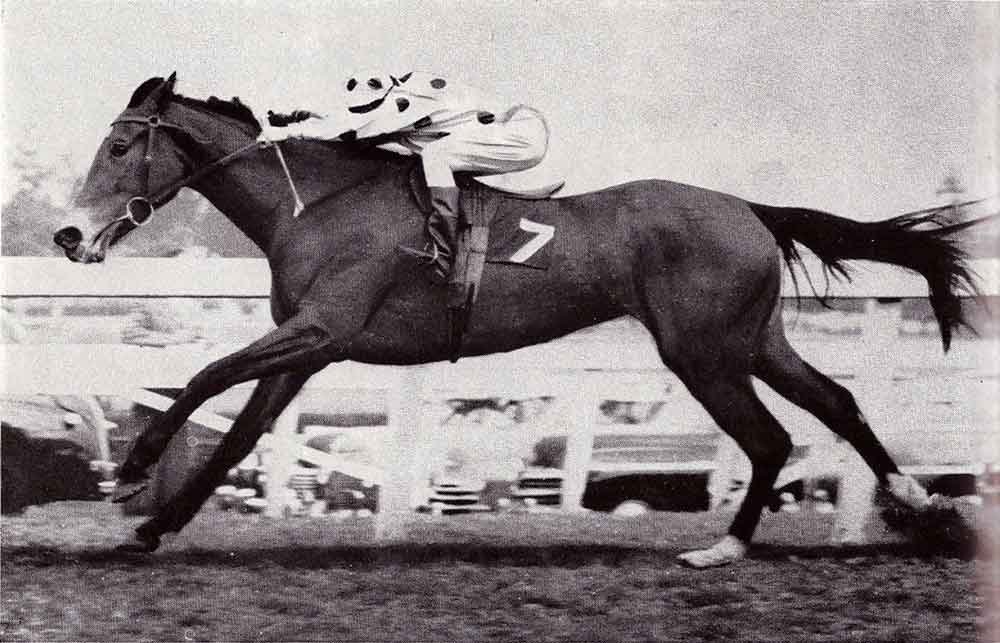

King’s Pact wins the 1953 Gr1 Champion Stakes at Greyville

Queen of the Turf in her day was the filly King’s Pact, a public idol and one of the most famous race mares ever produced in South Africa. She was bred by V.H. Russ at his Saulspoort Stud in the Free State and raced by the wife of trainer Willie Murphy. She was by His Excellency out of a mare by the Derby winner Windsor Lad. His Excellency was by Nearco out of a mare by the brilliant Diomedes, who was owned by Sidney Beer, the conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra. His Excellency had run fourth in the Two Thousand Guineas to Garden Path and never won beyond a mile, so there were naturally stamina doubts about his progeny due to both his breeding and performances.

After her first outing King’s Pact won seven of her eight races as a two-year-old. Subsequently it was shown that she was attempting the impossible on the occasion of her only defeat. Carrying 63.5 kg she was set to give 18.5kg to Preto’s Crown, who was later to win the Durban July Handicap. She was beaten by a length and a half, five lengths ahead of the third.

At three, King’s Pact won her first three races in Natal with ridiculous ease, including the Natal Derby over a mile and a half. This was really no test of stamina as the opposition was so poor that King’s Pact started at four to one on. She then won the weight-for-age Champion Stakes over a mile and a quarter, which was probably the limit of her stamina in really top class company, and by virtue of her age and sex, she was getting 12 kg from the second, High Peak, whom she was afterwards handicapped to give 4 kg in a handicap. She put this advantage to good use, her jockey, Flynn, sending her along to win in the South African record time of 2 minutes 2 seconds. She won by what is officially recorded as a distance, it was ten lengths or more. One wonders what time she might have recorded with something to race upsides with her.

After her victories in Natal she went up to the Transvaal, which was the first opportunity I had of seeing the filly that had become a legend. She was a bay with a mealy nose and two white fetlocks. She ran over the easy mile at Benoni and what impressed me most about her was her easy, effortless action. She came into the straight in this race some two lengths in front of the field but, in spite of a reminder close to home, she was only a length to the good when the post was reached.

Put back up the straight and carrying 60 kg she then spread-eagled a field of useful sprinters over six furlongs. She now had a record of twelve victories in her last fourteen outings so was allotted 54 kg in the Johannesburg Summer Handicap, the premier race in the Transvaal and one that has appeared under various names during the last few years and is, at present known as the Sun International. In those days, as a handicap, it was much harder for a good horse to win and a far greater test of a good horse that it is today. The 54 kg allotted to King’s Pact was a big weight for a three-year-old. Topweight was Flash On, who had won the race the previous year and gone on to win the Durban July Handicap in record time. He was set to give her 2 kg. The sex and weight allowance at that time of the year was 8 kg, so she was meeting the proven best older horse in the country, winner of the Johannesburg Summer and the Durban July Handicaps on 6 kg worse than weight-for-age terms; a formidable task even for one who was, with no doubt, the best filly ever bred in South Africa. Such was the public’s adoration that, with champion jockey “Tiger” Wright in the saddle, she was made a hot favourite.

By the day of the race the summer rains had made a quagmire of the Turffontein course, the going being particularly bad between the seven and the turn into the straight. I watched the race from a twenty foot high tower some five furlongs from home, between the two bends. As the field passed me the filly was on the outside and at the back of the field. Her lovely action had gone and she was sprawling badly. Once in the straight, where the going was better, she made up a lot of ground on the outside to finish fifth, just behind Flash On. It was in fact a very good performance in view of the weight she was carrying, the state of the going and that, in such conditions, a distance that must have been beyond her best.

In those days, before the camera, the usual story, if a favourite got beat, was that it was no good whereas, if it had won, then the race was a oner. The usual story started about King’s Pact. This time it was fuelled by the fact that a certain bookmaker, not in Johannesburg but in a neighbouring town had been freely laying the filly for big sums at slightly above the prevailing market price. The stipendiary stewards received instructions from the Local Executive of the Jockey Club to investigate. The first thing that these investigations revealed was that the rumour was correct and that certain bookmakers in Johannesburg Tattersalls had backed King’s Pact with the bookmaker, whose name had been so freely mentioned. Despite the fact that, in my own mind, I was quite satisfied with the filly’s run in the circumstances and convinced that she had been ridden entirely on merit, this discovery of this heavy laying against the favourite resulted in my being in a suspicious state of mind when, with another stipendiary steward (Kenneth Stewart), I visited the Tattersalls in the neighbouring town. Here we were welcomed by the secretary, who produced the betting sheets of the layer concerned. An examination of these showed that the bookmaker had backed the filly heavily at a good price before the weights had appeared and so had rightfully hedged when King’s Pact was shortening down to only six to four on the day of the race. So well had he made his book that he was wholly indifferent to the result, as he would have been as good a winner if the favourite had won as he would have been had it been a rank outsider.

King’s Pact’s next race was at her mercy, as it was at weight-for-age over a mile and she started at four to one on. She then travelled to the Cape and started at odds-on again next time out for the Cape of Good Hope Derby but a mile and a half was really too far for her; she ran a great race to be beaten a head by Syd Garrett’s Fair Weather. She returned to Johannesburg, was started over the mile and three-quarters of the South African St Leger and was beaten half a length by a good stayer in Derby Day. She turned the tables in the Natal St Leger over the same distance, in which Derby Day could only finish fourth.

A victory in the Durban Civic Centenary Cup over nine furlongs followed. She was handicapped at 55 kg for the Durban July, which must be the highest weight ever carried by a three-year-filly in this race, and ran fourth giving 11 kg to a colt of the same age. A fortnight later she came out gain for the Clairwood Winter Handicap, in which she was asked to give weight to the field. Despite this, she started favourite but was unplaced and another fortnight later came out yet again and was made favourite for the Chairman’s ’late in which she ran fourth. A week later she opened her four-year-old career by winning the Champion Stakes from eh odds-on Sea Lord. The handicappers now had control of her with weights like 61.5 and 61 kg and she ran four more times, the last two starting among those unquoted. One wonders why, she was pulled out for these last runs. She had done enough winning sixteen races. She was without any doubt the best filly bred in South Africa during my time.

King’s Pact had five foals, four of whom were winners – Royal Charter by Pachadermis won nine races, including an Autumn Goldfields Handicap at Turffontein,; Royal Monarch by Black Cap, winner of eight races including a Lonsdale Stirrup Cup at Newmarket; Kings Agree by Abadan winner of thirteen races including the Cape Merchants Cup; Queen’s Pact a filly by Abadan the winner of five races.

(source: Mordaunt Milner for Winner’s Circle Magazine – September 1986)

‹ Previous