Few discussions surrounding the use of drugs in US horse racing arise without mention of the race-day medication Furosemide. An anti-bleeding medication, commonly called Lasix or Salix, it is arguably the principal drug that differentiates the US medication regime from other major racing jurisdictions.

Elsewhere in the world, almost uniformly, race-day medications are banned.

It is at the heart of the latest anti-medication proposal – a push to incrementally phase out Lasix in the US, prohibiting its use in two-year-old races next year with a view to expanding the ban to encompass all races the year after.

The proposal was endorsed by 25 prominent trainers such as Todd Pletcher and Richard Mandella, as well as Breeders’ Cup officials Bill Farish and Craig Fravel; in a call to arms to other racecourses owners, Frank Stronach, whose Stronach Group owns six US racecourses, urged a collective ban of Lasix at all tracks.

Stronach subsequently announced that he would offer a series of Lasix-free two-year-old races next year at Gulfstream Park, a racecourse under the Stronach Group banner.

The Pletcher-led proposal drew fire from the opposing camp. Rick Violette, president of the New York Thoroughbred Horsemen’s Association, argued that “the vast majority of horses bleed” and that “Lasix is the safest and most effective treatment we have available to treat this condition”. His was not a solitary voice – the majority of horsemen’s organisations in the US united against a Lasix ban.

What has largely defined this long-standing tug-of-war is the belief by most on either side of the table that theirs’ is the stance more aligned with horse welfare – that to ban a drug that has been proven to be effective in treating bleeders is as cruel and dangerous to racehorses as it is to administer it. But after years of intractability the latest proposal, with its ringing endorsement from so many figures in the racing war cabinet, appears to be one of the most significant pushes yet for Lasix reform.

Nevertheless, with more than 90% of North American racehorses given the drug before competing, the winds of change will have to blow with some force before wholesale changes to the race-day medication rules can be brought about.

Why do horses bleed?

Why do horses bleed?

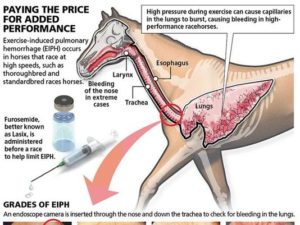

Racehorses are unique, in that they are one of very few animals known to suffer Exercise Induced Pulmonary Hemorrhage (EIPH) (more commonly referred to as bleeding), Professor Ken Hinchcliff, dean of veterinary and agricultural sciences at the University of Melbourne and co-author of a series of comprehensive studies in recent years looking into the effects of Lasix on racehorses, told the Guardian. One of the causes of EIPH is a four-fold increase in pulmonary blood pressure when horses exercise or compete.

“If you take a horse out and exercise it, then the blood pressure leading from the artery on the right side of the heart to the lungs increases from about 25mm of mercury [pressure] to about 100mm of pressure,” he said. “You don’t see anything like this in humans, for example.”

This marked increase in pulmonary pressure means that small capillaries in such horses’ lungs are prone to rupture, said Paul Morley, professor of epidemiology and biosecurity at Colorado State University and co-author with Hinchcliff on a number of studies.

“It’s in those capillaries next to the alveoli near the bottom of the lungs that the best evidence suggests EIPH related bleeding occurs there,” he said, agreeing with Hinchcliff’s assessment concerning the rare biological mechanics of thoroughbreds. “Through a ‘contraction’ of the spleen, they are able to increase their numbers of oxygen-carrying red cells dramatically over what other species can do when exercising.

It’s just one of many evolutionary specialisations that make the horse an exceptional athlete.

The severity by which horses bleed is graded from zero to four. At zero, an endoscopic examination (scope) of a horse’s lungs shows no visible traces of blood. At grades one, two and three, the amount of blood in the lungs increases, though blood is not necessarily visible in the nostrils. At grade four, epistaxis occurs – and blood is visible in either or both nostrils.

Between 0.1% and 0.2% of all starters suffer epistaxis. Those who do exhibit varying amounts of blood in the nostrils, with a few having large amounts, said Morley. He disagrees with suggestions that EIPH is painful.

“There are not pain receptors of the type we’re talking about in the deep portions of the lung where the bleeding occurs,” said Morley. “In most EIPH events horses might have some sensation that this has occurred. For horses that have severe bleeding, they may have some sensation that there’s fluid in their airways as much as if you have mucus in your airways.”

Nevertheless, numerous studies have linked epistaxis to sudden death in racehorses – though this is “extremely rare”, said Morley.

According to Hinchcliff, it is very likely that all horses bleed to varying degrees, and “certainly there is evidence that most horses do”. A horse’s performance will be compromised if it bleeds at a level two and higher, though Hinchcliff said that the threshold is an approximate one.

A 2005 study of 744 racehorses in Australia – where Lasix is banned on race-day but permitted for training purposes – found that horses that bled to a degree less than one were four times more likely to win than horses that bled to a level higher than two.

Of the 415 horses in the study which developed EIPH, 273 bled to a level of one or less. These horses performed as well as a horse that had no trace of blood in their lungs, and were nearly twice as likely to finish in one of the top three positions compared with horses with an EIPH of grade two, three or four. One hundred and one horses were diagnosed with grade two bleeding, while 25 bled to grade three. Thirteen horses had grade-four EIPH. The more severe the disorder, the further behind the winner a horse was likely to place.

A subsequent study of 167 South African racehorses – a like-for-like study comparing Lasix with a saline placebo – corroborated, to a certain extent, the findings of the 2005 study. Researchers found that 20% of those horses not given Lasix did not bleed, while 45% bled at level one and 25% bled at level two. Ten percent of horses examined bled to a level higher than two. Thirty-five percent of the horses bled significantly enough to impair performance, with 1% bleeding to level-four severity.

The frequency with which horses are put under the strain of strenuous exercise and the number of times they are subsequently scoped are also factors. Between 43% and 75% of racehorses exhibit signs of EIPH based on the evidence of one scope. The 2005 Australian study showed that nearly 100% of horses scoped after three successive strenuous workouts showed some bleeding by the third endoscopic exam.

How does Lasix work?

How does Lasix work?

Currently, in the US, Lasix must be administered intravenously no later than four hours before a race and at a quantity no larger than 500mg. Its effects as a diuretic are swift.

“A horse can pass between 10 to 15 liters of urine in the first hour after Furosemide is administered,” said Hinchcliff. “Whereas a horse throughout the normal course of the day would only produce about 10 to 15 liters of urine. So it markedly increases the rate of urine production.”

Typically, a horse given Lasix is not permitted to drink in the four hours before it races. “And if horses aren’t permitted to drink, the result in water loss is that horses are then on average 10lbs to 20lbs lighter,” said Hinchcliff. “If they are permitted to drink, they rehydrate and pretty much restore their weight in a short amount of time.”

How Lasix is thought to work is essentially two-fold. “It results in their blood PH becoming a little bit higher so it becomes less acid, and that might be important,” said Hinchcliff.

The other way Lasix works, Hinchcliff said, is believed to be a consequence of water loss significantly lessening pulmonary blood pressure: “If you give a horse Furosemide, that pressure increases about three times rather than the four times as is normally the case.”

Lasix, Hinchcliff said, is “remarkably safe” for a drug administered so frequently – in the short term. “We don’t see problems at the racetrack that are clearly associated with the administration of Furosemide.” Rather less certain are potential long-term health consequences.

“There is much speculation that Lasix might have long-term health consequences to horses,” said Hinchcliff.

I’m aware of no evidence that horses that have been administered Furosemide are at greater risk of any particular disease. But I think we should be cautious that there could be long-term adverse affects.

What is more certain is the drug’s potency as an anti-bleeding medication. The 2009 South Africa study found that horses were three to four times more likely to have any evidence of bleeding without furosemide, and were seven to 11 times more likely to have severe bleeding without it. None of the 152 horses given Lasix bled to a degree higher than two.

Is Lasix a performance-enhancing drug?

Is Lasix a performance-enhancing drug?

While the effectiveness of Lasix is in no doubt, question marks over exactly how it manages to improve racehorse performance lead to concerns about its role as a potential performance enhancer.

If the improvement in performance is a consequence of Lasix-induced weight loss, said Dr Richard Sams, director of HFL Sport Science, a laboratory that performs drug testing for the Kentucky Horse Racing Commission and the Virginia Racing Commission, a shadow is thrown over whether Lasix is a legitimate medication or a performance enhancer.

“I think the mechanism by which Furosemide allows horses to have superior performances is unclear,” he said. “If the mechanism by which it allows a horse to run to its potential is because horses are running 10kg lighter, then I think the handicapper should comment on whether that’s allowing horses to run to their potential, or whether it’s allowing them to run beyond their potential. When you think about it, 20lbs on a horse is a big handicap.”

Trainers in the US have for a long time turned to Lasix to tackle the problem of bleeding – the Kentucky Derby winner Northern Dancer was given Lasix before his record-breaking performance in the 1964 race. It wasn’t until the 1970s that Lasix began to fall under the jurisdiction of racing authorities, with legalisation in 14 states by the start of 1975, though with no uniformity surrounding dosage times and levels. Even back then, critics of Lasix voiced concern about its properties as a masking agent for other drugs.

“In 1983, the predecessor to [the Association of Racecourse Commissioners International] adopted a resolution that banned the use of Furosemide in all of racing,” said Sams, “the reason being that a lot of substances were detected with great difficulty and in some cases weren’t detected at all during that period of intense diuresis [heavy urination] that followed administration of Furosemide.”

Lasix works as a masking agent during diuresis, said Sams.

It dilutes the sample during the period of diuresis and makes it more difficult to find those substances that are not re-absorbed.

Opposition to the ban from trainers prompted a study that found 250mg of Lasix could be safely administered four hours before a race without affecting the detection of a list of drugs that were not permitted on race-day. This set of guidelines was subsequently adopted, incrementally, by racing jurisdictions throughout the country.

“We reported back that under those conditions all of the drugs we chose to investigate were detectable in the form of our sample,” said Sams. “As soon as the period of diuresis is over, the other drug or drugs are still there in the concentrations that you would find them without Furosemide ever having been administered.”

Since then, the permissible level of Lasix has been increased to 500mg. According to Sams, there has been no subsequent comprehensive study of the effects of Lasix on every current permissible medication; nor has there been a study determining whether the increased dosage level is similarly consequential.

“But we know that with 500mg, the period of diuresis is not extended,” he said. “And since the effect is due to diuresis, I don’t anticipate any substantial effect on detectability.”

‘Horses are not like fruit flies’

‘Horses are not like fruit flies’

In 1960, the average start per horse per year was 11.31 – a peak in the record books.

In 1975, the year Lasix enjoyed wide introduction into many jurisdictions, the average start per horse was 10.23.

In 2013, horses started on average 6.32 times a year – a statistic cited by many to prove that Lasix and other drugs are weakening the breed. Indeed, a 2004 South African study, “A genetic analysis of epistaxis as associated with EIPH in the Southern African Thoroughbred”, argues that EIPH is an inherited trait.

Dr James MacLeod, a veterinarian and scientist at the Maxwell H Gluck Equine Research Center, urges caution before turning to genetics to produce a definitive answer. “For any given trait, one of the big questions is: ‘To what extent are genes responsible for that issue to begin with as opposed to environmental variables?’ For traits as complex as bleeding and racehorses durability, several inherited genes will likely be important, but so will a number of environmental variables.

“Horses are not like fruit flies that hatch and reach reproductive maturity in only 10 days – there are multiple years involved in the generation time. And so, when you think about the distribution of several deleterious genetic changes through most of the thoroughbred population, it would take much longer than the 30 to 50 years that people are saying there’s been this profound drop in racehorse durability. As such, you cannot explain the drop in the number of starts strictly on a genetic model – the math just doesn’t work out.”

“Rather than lean towards genetics to explain the marked drop in starts, New York based trainer Kiaran McLaughlin, one of the 25 signatories on the latest proposal to phase out Lasix, believes horses are simply taking longer to recover from the diuretic effects of Lasix.

“I don’t think like a lot of people do that [banning Lasix] will kill starts per horse – it might do the opposite actually,” said McLaughlin, who in 2011 had rallied in support of Lasix.

I think people would be surprised how few horses actually bleed out the nostrils – it’s really not that many. And even if some of them bleed a little bit, they’re still going to perform and perform well.

For the past two years, McLaughlin has cut considerably the number of two-year-olds he runs on Lasix. “Once we know they bleed,” he says, “we do obviously work them on Lasix, however, and we will sign them up for Lasix on race-day.”

” Only a small percentage of those which ran without Lasix bled”, he said.

“It’s very interesting. For those two years, we scoped every horse after they ran and most horses after they worked to see where they stood, and I have to say that less than 5% of the horses we ran without Lasix bled at all,” said McLaughlin, who believes his simplified Lasix programme over the past two years proves that trainers mistakenly use Lasix as a wholesale preventative rather than an imperative.

“I think it’s abused in America to the point where 90% of two-year-olds are on it right away, so you don’t know if they’re bleeders or not and you don’t know if they need it or not,” said McLaughlin.

A ban on Lasix would certainly necessitate an adjustment in the way horses are trained and raced, he said.

Maybe they shouldn’t be running so often or as far or in as tough races. And if they are bad bleeders, maybe they need to be stopped on or retired.

This leads to another frequently raised comparison: that climate, training facilities and racing programmes make Lasix more necessary in the US than elsewhere.

Rick Violette alluded to the same disparity when he said “to not have Lasix available for horses competing in the sweltering heat and humidity of non-winter Florida racing is a recipe for disaster”.

Unlike the US, where the majority of horses are trained during a short window of time in the morning within the tighter confines of the racetrack, racehorses trained in Europe are, by and large, exercised for longer and in quieter surroundings more conducive to keeping horses that bleed settled and calm.

But McLaughlin counters that the facilities used by the majority of American trainers are no different to some jurisdictions that implement a race-day medication ban.

“I trained in Dubai for ten years and their facilities are very, very similar to America,” he said. “We trained on dirt in the heat and we went left-handed. I just don’t agree with that.”

He said that with a known bleeder, he would try to replicate the diuretic effect of Lasix by limiting the amount of water that horse was given before a race – a practice known as drawing.

“We will obviously pull their water early in the morning, try to draw them a little bit,” he said. “And at the end of the day, there are vitamins out there you can try that are legal.”

According to Professor Paul Morley, however, the only proven remedy to bleeding is Lasix. “There’s a whole grocery list of anecdotal testimonies suggesting what might be helpful,” he said. “The only thing that really has been proven to help is Furosemide.”

Nasal strips are common. You can see those in jurisdictions that allow them. There is some evidence to suggest that they maybe helpful but again, you’d have to add the caveat that most of the others haven’t been examined with the same level of rigor as Furosemide has.

Morley drew attention to the ethical concerns surrounding the practice of drawing a horse to replicate the diuretic effect of Lasix.

“It’s possible that people could achieve a similar level of volume reduction in the vascular compartment by not watering the horses,” said Morley. “So, if you didn’t do that for a period of something like 24 or 36 hours, you might achieve a comparable level of volume contraction.

“But then you might ask the question, which is worse? Which would you prefer to have? Simply removing Furosemide from the field doesn’t answer all the questions – it raises some as well.”

Lasix and British racing

Lasix and British racing

Though Lasix is banned as a race-day medication in the UK, it is permitted for use during training. Proponents of Lasix point to comments made by the trainer Nicky Henderson during his 2009 hearing for administering the anti-bleeder medication tranexamic acid, that “plenty of trainers” were using the banned medication, as proof that other racing jurisdictions are bedeviled with the same problem.

When I asked Alan King, one of the UK’s leading duel-purpose trainers with 14 winners at the Cheltenham festival, how he medicates bleeders, he argued that anti-bleeder medications such as Lasix have never been a part of his training regime. “I’ve never had the need to use it,” he said. “Though I don’t think [bleeding] is as much of an issue here in this country.

“If a horse is a really bad bleeder we might try to dehydrate them, take their water away the morning of a race, something like that, but that’s as far as we go,” he added, though he said that less than 10% of his horses bleed, and few of those are bad bleeders. “Mostly, we turn them out as much as we can.”

Which leads back to that frequently raised suggestion: that climate, training facilities and racing programmes make Lasix more necessary in the US than elsewhere.

A question of welfare?

Other prominent figures, however, approach the issue from another angle – that the very public debate surrounding Lasix is overshadowing efforts to make changes within the industry that would be more critical to racehorse safety and welfare.

Maggi Moss, who owns a large string of horses from her base in Iowa and is a long-time animal-rights advocate, said:

“My concern is this: while a lot of people on this bandwagon are concerned about banning all race-day medications, I’m concerned about all of the other things we’re doing to horses.

As a matter of priority Moss, who says her horses are never shockwaved and are only administered intra-articular injections on the advice of veterinarians, and not to mask unsoundness, would like to see those drugs and treatments more directly tied to soundness given the same public scrutiny as Lasix.

“There are too many unsound horses running – horses that need breaks, horses that should not be running and are having soundness problems masked by race-day or pre-race medications,” she said. “What about discussing shockwaving and multiple injecting? What about discussing breeding unsound horses?

“What I see is a real problem as to the welfare of racehorses is that horses can have no after-life or pain-free life due to this sort of abuse. I do not understand why it’s OK to use cortisone or shockwaving or new boutique drugs, never giving horses breaks and continuing to run unsound horses, and then [I] try to understand how Lasix became so urgent and the topic of the day.

“Shouldn’t the welfare of the horses be the concern?”

www.theguardian.com