The fact that the majority of horse owners the world over are still deworming horses as they did 40 years ago – by the calendar – regardless of need or species affecting the horse, may have grave consequences, writes Dr Karl van Laeren of Worm-Ex Lab.

There are four major groups of parasites that need to be considered:

1. Small Strongyles or Cyathostomins;

These worms live in the gut wall of the cecum (the very large equivalent of a human’s appendix but designed to digest grass) before maturing and migrating into gut lumen or cavity They often occur in numbers exceeding 100,000 worms in the gut wall. As adults they migrate out of the wall into the intestinal cavity where they live on bacteria and protozoa and cause little harm. This is where reproduction and egg production occurs and is the principle egg seen in horse’s dung. If a rare mass emergence of larvae from the gut wall occurs, this could be fatal in young horses.

2. Large Strongyles;

These worms are the real “bad boys” of yesteryear. They migrate beyond the gut wall and into the arteries of the abdomen, or in the liver and other abnormal sites like the testicular arteries in stallions or the aorta, before it splits into the leg arteries. Left untreated, they form masses, called thromboses, which can break loose, leading to a blockage of the arterial tree and starving the

intestine of blood supply, which causes areas of the intestine to die off, resulting in colics and other complications. Fortunately, nowadays Large Strongyles are a lot more rare, thanks to the deworming efficacy on many studs.

3. Non strongylid Gastrointestinal nematodes (parasites) or GIN’s

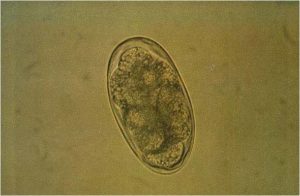

These include Parascaris equorum (Ascarids), Habronema sp. and Draschia megastoma (Summer sore worms), Oxyuris equi (pinworms), Trichostrongylus axei (stomach bankrupt worms contracted from cattle and sheep especially in winter rainfall areas. This is the only parasite horses and ruminants share in common) and Strongyloides westerii (transmitted in mare’s milk to foals). On studs and racing stables the Ascarid worm that develops after passing through the lungs of horses is the most spectacular due to its large pencil-like size. The eggs of this GIN are thick walled and very well designed to survive in the environment for years, overcoming freezing cold or hot dry spells. Because these parasites pass through the horse’s respiratory system, left uncontrolled, they can result in respiratory issues like “the snots” as well as intestinal blockages, leading to colics and associated complications. Ascarids developed resistance 20 years ago to the newest generation of dewormers.

4. Tapeworms

Tapeworms undergo an indirect life cycle, needing a forage mite to complete the life cycle.

Parasite control is effected by the administration of anthelmintics (a group of antiparasitic drugs that expel parasitic worms (helminths) and other internal parasites from the body by either paralysing or killing them and without causing significant damage to the host).

Most studs deworm all horses willy-nilly two to four to even eight times a year, regardless of age or immunity.

Anthelmintic Resistance

The more we, as humans, get exposed to antibiotics the more likely a bacterium will mutate into a super bug. The same principle applies to our horses’ parasites or GIN’s. The more dewormers used per year, the greater the likelihood of resistance occurring and the faster it is likely to happen. A dewormer is a tool to rid horses of GIN’s but it is also a selector for hardy resistant worms as what’s left alive after a deworming have been specifically selected to withstand that particular dewormer.

Anthelmintic resistance (termed AR in the scientific literature) occurs when worms get exposed to an effective dewormer, but fail to respond satisfactorily. A satisfactory response is a reduction of at least 95% on the pre-worming worm egg count. So, if a horse shows 1000 eggs per gram of dung pre-deworming, they should have 50 or less eggs two weeks after deworming to meet the 95% acceptance level. If not, they are showing signs of AR.

Small Strongyles are the most common parasites in horses and also the most commonly susceptible to AR. However, there are over 40 species of Small Strongyles and only one or two may initially have mutated into a resistant species. So, a count may only drop from 1000 eggs per gram of dung to say 150, which indicates only 85% reduction. This is an indication that some worm species are not being effectively destroyed and it may be worth trying another dewormer to rid the horse of the remaining worms. This war against parasites is won or lost by the accumulation of small victories and/or oversights.

As young horses carry the highest worm burdens and may be exposed to up to eight dewormings per year, this is the portion of the horse population that has shown the greatest tendency to develop resistance.

Breeding A Better Worm?

In essence, resistance is occurring in the Performance Horse and Thoroughbred studs and has the potential to spread to in contact horses. To date we have encountered no less than 60 such young Thoroughbreds that fail to clear fully after ivermectin dewormers. In such cases, we then advocate moxidectin dewormers which may reduce the burden some more. However, these horses never drop to the mandatory 95-99% reduction levels one would expect with macrocyclic lactone dewormers (the family of drugs containing ivermectin, abamectin, the cattle dewormer, doramectin, and moxidectin).

There is evidence of Macrocyclic lactone dewormer resistance in sheep, cattle and in horses. We diagnosed our first case in a horse from the Eastern Cape in 2016. A new molecule, monopantel, developed in New Zealand is now available for sheep and goats but alas, the first cases of resistance were reported in 2013 in NZ.

Horses, however, have no new “get out of jail solution” if resistance is encountered, as monopantel’s safety in horses and in pregnant mares is not assured. We are having to revert to older families of drugs or a combination of deworming drugs to clear resistant parasites. Stomach tubing with up to three drugs has been required in some Ascarid infections.

As long as horse owners and even their veterinarians remain confused or unaware of the risk factors of repeated deworming with, moxidectin in particular, GINs, especially in young horses, are prone to encourage and select for resistant genes to evolve and disseminate to other horses sharing the same paddock space. Stud farms are breeding good equine genetics (bloodstock) through selecting strong compatible pedigrees, but inadvertently, excessive and unnecessary dewormings are breeding bad persisting parasite genes with a propensity to show resistance to drugs that previously proved highly effective.

Growing Problem

Anthelmintic resistance is now a worldwide phenomenon. Just think of the old days were one syringe of dewormer was truly BROAD SPECTRUM. This term is now a dream of the past as Ascarids, pinworms and now Small Strongyles all show signs of AR.

The Southern African evidence pertaining to AR has mainly come from the Thoroughbred studs producing stock for racing purposes. Usually this trend to AR is only noticed when these horses arrive at the few training establishments practicing selective deworming. Selective deworming is an evidence-based deworming protocol where only horses with over a predetermined threshold level are dewormed. Studs and racing stables should do worm egg counts (WEC) and especially feacal egg count reduction tests (FECRT) to establish the efficacy of their deworming drug of choice and whether AR is present in their herd. “Is our deworming achieving a 95% plus outcome post worming?” should be on every forward-thinking stud personnel’s mind.

If doing these tests on the entire draft of yearlings and two year olds in one’s care is initially unattractive, one should consider testing a sector of the stud to establish whether the drugs one is employing are producing the desired outcome. A reduction of 95% plus should be achievable on an individual basis and certainly on a stud basis to ensure that one’s deworming protocol is effective.

Oddity

The one clear oddity about AR is that it never shows up in an entire draft of horses. One or more individuals may be affected, while other members of the herd may show no signs. So, throw one’s net out as far as possible as the problem is still very selective in distribution. Only by looking critically at one’s deworming methods are we likely to avert a looming disaster.

Trying new technologies, we tend to compare this in our minds with what we perceive to be a perfect solution, global across-the-board deworming. Unfortunately, the latter is far from a perfect solution and it behooves stud managers, racehorse trainers and veterinarians to realize that performing WEC is the gold standard in parasite diagnosis. Not doing this is leading to an already occurring dilemma of up to 10% of 2 year olds presenting with resistant worms arriving at the training yards.

Acknowledgements. The term “Global Worming” was coined by Dr Rose Nolen-Walston and cited in an article written by Ray Kaplan the Equine Parasitology scientist from the University of Georgia, USA .

An Inconvenient Truth: Global Worming and Anthelmintic Resistance.

Veterinary Parasitology, 2012: Vol 186 Issue 1 & 2 pgs. 70-78. Kaplan R et al.