There is inherent danger in mixing science with the world of horses and to quote a recent internet find ‘If you’re going to tell the truth, it’s best to keep one foot in the stirrup’. I guess it depends very much on whether one considers science and empirical data as ‘the truth’, but it is interesting to see the worlds of racing and science collide.

Dr David Marlin is a scientist with more than 25 years’ experience in physiology and biochemistry. He has such a fascinating background that a full CV would take up most of this page. His main areas of professional interest are exercise physiology, nutrition, fitness, training, performance, thermoregulation, competition strategy, transport and respiratory disease. He has written over 200 scientific papers and book chapters, and is the author of one of my favourite books, Equine Exercise Physiology. He was good enough to chat to me about his favourite subject.

Not built for the job

“If horses had legs twice as thick, they’d probably never fracture, but they wouldn’t be as fast. Horses have evolved for speed. They have thin bones, thin tendons and all their muscles up near the body, to allow their legs to move very fast. That’s why the Thoroughbred is such an elite athlete. The down side is that it’s always on the point of failure. A 500kg horse has evolved structures to carry 500kgs of load. The safety margin of bones, joints and tendons is about 20%, so every time you put a rider on, you’re overloading structures which are close to failing point anyway.”

Genetics

“When someone gives me a list of 10 horses and asks which one to buy, I prefer not to know the pedigrees as it tends to cloud the picture. Pedigree only tells me what I can expect to have in front of me, not what I do have, which is what counts. Genetics isn’t 1+1=2 a lot of the time. You may know the bloodlines, but not the genetics and those are two very different things. They say breed the best to the best, but heritability of performance is about 15%. We are able to measure stride length, test for muscle type and scan the heart size and I’m happy to make decisions based on that information, but for now it’s a numbers game and will remain so until people start using genetic testing.”

Choosing an athlete

“There are a few general rules, which will vary depending on the optimum distance you want. If I wanted the perfect racehorse for the classic distance of a mile and a half, I’d look for a horse with a large heart with relatively thin walls. It would need the correct muscle type, good conformation and the right temperament. By that I don’t necessarily mean a horse that’s nice – lots of the good ones are quite savage, or have something unusual about them – but you need something that will withstand training.”

Nutrition

Horses have small stomachs relative to their size, limiting the amount of food they can take in. The stomach has a capacity of approx 15 litres and empties when it is 2/3 full, regardless of whether the stomach enzymes have finished processing the food or not. “There seems to be a belief that you need to shove loads of feed into them. Although high performance horses need carbs, one shouldn’t be trying to feed it in 2 large meals a day. Large amounts of high energy feeds have a negative effect on the hind gut and one runs the risk of ulcers, potential hind gut disturbances and colic. You don’t want starch reaching the hind gut undigested as it results in all those problems, so it’s important to feed roughage first to slow the passage of the food.”

As with human athletes, you can dramatically affect a horse’s performance by changing their diet. Feeding a human sprinter on a low protein / high fat diet will reduce performance. In the same way feeding a long distance runner a high protein / low fat diet will reduce their distance ability. It is the same with horses and one needs to weigh up what each individual needs to maintain their condition in relation to their workload. The take home message is that nutrition has to be individualised if you are to optimise the performance of each horse.

Saddles

“The sport horse industry has been aware for some time that not every saddle fits every horse and that one can have a tremendous influence on how a horse goes by changing its saddle. Yet you’ll have an exercise rider who goes around with one saddle and puts it on every horse. One of the biggest things we see affecting performance is saddles that don’t fit, which can seriously hamper a horse’s chances of performing to its potential. It would probably cost about $300 for a decent saddle for horses that are already costing $50k a year, but it’s $300 people generally don’t want to spend.”

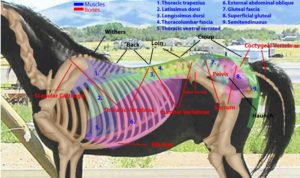

Backs

“Back injuries in the racing industry are virtually ignored. Eighty percent of horses we see show damage to their spinous processes, but the racing industry is in denial about saddles and backs. I think they are underdiagnosed and think it’s undervalued as a cause of poor performance.”

“Look at the effect of a small amount of back pain in a person and what that does to them. Even a small amount can reduce a world class athlete to a virtual quadriplegic. Your back is part of your core strength and it is the same thing in a horse. Back pain can affect how horses move in other ways as well. Unfortunately the only way we can really understand the implication of back pain in horses is with local anaesthesia. When you eliminate back pain in horses, one sees a tremendous improvement in performance.”

Epistaxis / Bleeding

“All horses break blood vessels in their lungs, even at a trot because the membrane that separates the red blood cells from the airspace is 100th of the thickness of a human hair. It’s less surprising that horses bleed and rather that they don’t bleed more. It is a consequence of intense exercise and the more they race, the more damage is done to the lungs and therefore the severity of the bleeding increases over time.”

“All horses break blood vessels in racing. Although only a small portion bleed to the extent that it is visible at the nostril, if you go deep into the lung you will find blood – always. The reason that some horses bleed more than others is multi-factorial and complex, but it is important to understand and investigate severe episodes.”

Lasix

“Lasix is a human drug usually prescribed for conditions like high blood pressure or pulmonary oedema. Any medic will tell you that one starts off with a standard dose, but soon need to increase it. Your kidneys work out what’s going on and start to adapt, so you develop a tolerance. I suspect the same is true in horses.”

“Lasix is a human drug usually prescribed for conditions like high blood pressure or pulmonary oedema. Any medic will tell you that one starts off with a standard dose, but soon need to increase it. Your kidneys work out what’s going on and start to adapt, so you develop a tolerance. I suspect the same is true in horses.”

“Lasix does reduce the severity of bleeding in horses and there have been studies into its use, but so far these have been limited to cases where Lasix was used once – no one has looked at what happens in the 2nd, 3rd and 4th race, so there are no studies to show whether it’s effective in reducing bleeding on a chronic basis. In the USA, a horse will produce its best performance the first time it runs on Lasix. If they carry on being administered Lasix, performance tapers off until they run at the level they were before. I suspect you’ll find the same thing in relation to bleeding – that it works well if used occasionally, but not chronically.”

“Interestingly there is very good data to support the efficacy of nasal strips in treating bleeding. I don’t know why there’s a perception that something that comes out of needle is better than something that doesn’t. Nasal strips are effective and I use them wherever I can as part of the management of horses that bleed severely.”

Medication

“I am anti the use of medication and think allowing race day medications would be a retrograde step. I think people will push the boundaries and simply use medication to push horses harder and we’ve already got problems with how horses are being trained now.”

“I am anti the use of medication and think allowing race day medications would be a retrograde step. I think people will push the boundaries and simply use medication to push horses harder and we’ve already got problems with how horses are being trained now.”

“If you told a lay person that we have developed a sport where every time the horse exercises, it damages its lungs, but we are proposing using a drug that helps reduce that damage, the danger is that someone says ‘why not stop doing the exercise? Why train so hard?’ It’s the same argument with Bute. Instead of legalising anti-inflammatories, why not just reduce training, and thereby reduce the need for the medication?”

Training methods

“I would say most racehorses and sport horses are probably trained ineffectively, rather than too hard. People look at how human athletes train and apply certain features, but forget others. For example, as they approach a competition, human athletes will back off training, maintaining the intensity, but reducing the number of hours they train. It’s called tapering and people typically start tapering 7 – 10 days before a competition. You never see that in racing. Racehorses are normally sprinted up a few days before a race. If you galloped a horse on a Wednesday, by Friday it would probably have recovered, but it depends on how long and fast you galloped and how much glycogen was used. Two days is probably the minimum in terms of allowing the muscle glycogen to restore and soreness in the muscles to recover.”

Science / technology

“When I came into racing approximately 30 years ago, it was straw bedding and oats and I could predict what each trainer would be doing each day. There have been huge advances in science and technology. You can now put a little sensor on a horse and get exact data on its speed, distance, stride frequency, stride length and heart rate and analyse exactly what work it did. We’ve seen a lot of changes in terms of surfaces, medication, diagnostic technology, nutrition, research and risk factors and yet we are still facing much the same problems, so something is not quite right and I think the industry needs to be a little more aware of the PR side.”

“Consider this: one of the UK’s most established newspapers ceased to exist because of an orchestrated social media campaign. We are seeing it in the FEI in the endurance discipline and the current situation may split the sport. If people form a campaign and it gets momentum, racing could easily go the same way.”

“There have been a lot of studies looking at the risk factors for say fractures and we know what a lot of the risk factors are now – doing certain work ratios or jumping in intensity too quickly. The question is why trainers are not adopting recommendations to reduce the instance of fractures? It could be that trainers apply the recommendations, but find horses don’t run as well. It could be that some things we have to do for horses in training to win on the track simply are detrimental. Most trainers aren’t scientists and don’t evaluate things critically – they tend to work on what they’ve got in front of them and to some extent that is good. In order to apply information correctly, you do need feel and intuition as well – which is probably why I don’t train racehorses!”